memory

Forget This Book

Whether we remember them or not, the details of life still drive our lingering emotions. ...

The Memory Hole

An empty bucket, a Zappos shoebox, potting soil, a collapsed dog crate, a dog bed, a broken lamp wrapped in duct tape, some synthetic firewood—the flotsam and jetsam of the half-forgotten years. These leftovers from past lives accumulate in suburban garages as the people who once wanted them get older and older. Useless and unnoticed, they yet cling on doggedly until time does its work, their owners depart for good, and new people move in and take them to the dump.

But this particular jumble of detritus has been rescued from oblivion and given a new home in the eternal archives of US history. For it included another item: a damaged box containing classified documents relating to America’s failed war in Afghanistan. That box, like Pandora’s, contained a whole world of trouble. From it has emerged the reality that the Democrats have been trying to evade—the vulnerability created by Joe Biden’s senescence.

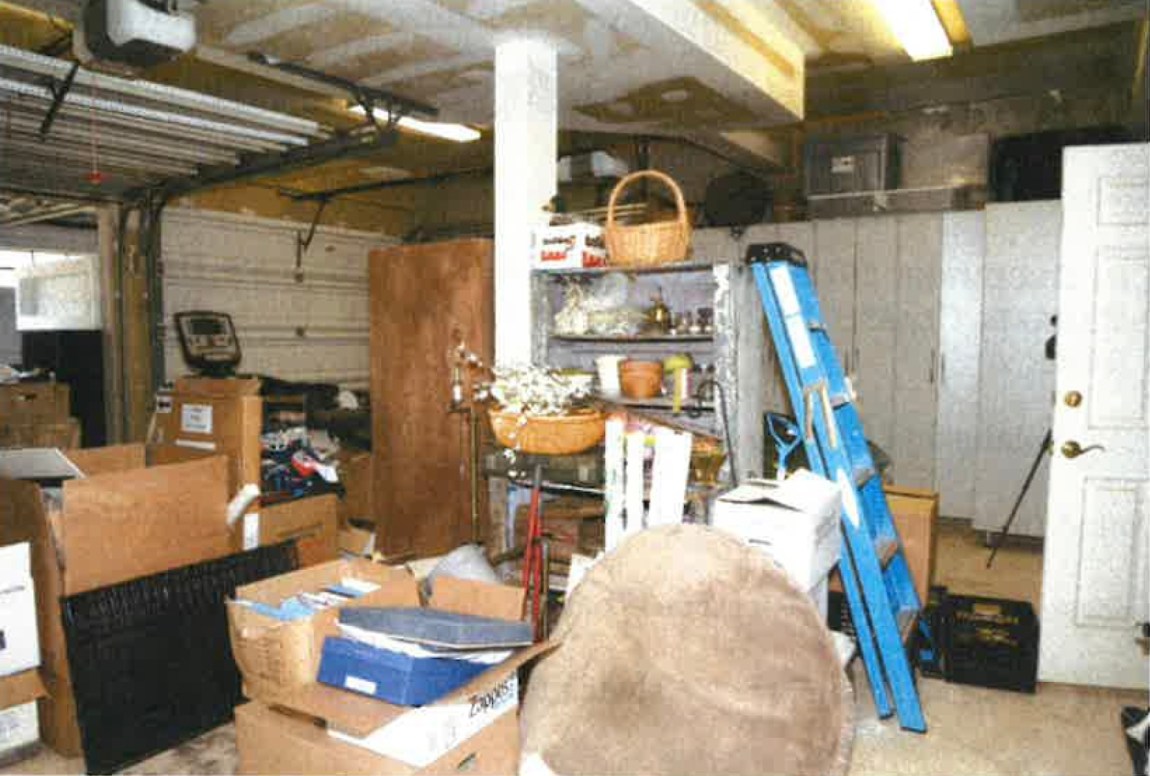

In the report of the special counsel Robert Hur into Biden’s retention of official documents at his homes, there is a photograph taken in the garage of his residence in Wilmington, Delaware, by an FBI agent in December 2022. It shows a familiar chaos of discarded objects: the console of a treadmill, red drain rods and a blue ladder, dried white flowers drooping disconsolately from a basket—kept, presumably, because they once meant something. Among them is the open brown cardboard box, its left side tattered and dented, from which peep the blue and white tops of documents Biden used when he was vice-president and then forgot to return after he left office.

US Department of Justice

A photograph of Joe Biden’s Delaware garage reproduced in the special counsel’s report, December 21, 2022

Seen differently, it might all be a conceptual art installation, a mordant commentary on the way America’s longest war has already been consigned to the national garage as just another dust-gathering discard. Instead, it dramatizes a much more literal question of memory and forgetting. Hur used the opportunity of his report to characterize Biden as an “elderly man with a poor memory” and “diminished faculties.” In his disastrous press conference of January 8, responding to Hur’s report, Biden in turn made a verbal slip that seemed to contradict his insistence that “my memory is fine,” describing the Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi as “the president of Mexico, el-Sisi.”

The irony here is that Hur uses the location of the box of Afghanistan-related papers in the garage in Wilmington as evidence of Biden’s likely innocence of any crime:

A reasonable juror could conclude that this is not where a person intentionally stores what he supposedly considers to be important classified documents, critical to his legacy. Rather, it looks more like a place a person stores classified documents he has forgotten about or is unaware of.

Hur, in the body of his report, is actually quite good on the subject of forgetfulness. He recognizes that Biden, after he left office as vice-president, had such long experience of reading official documents that they might not be especially memorable to him: “Mr. Biden, after all, had seen classified documents nearly every day for the previous eight years.” In relation to the contentious documents that Biden retained, including a memo he wrote to then-president Barack Obama opposing a “surge” of US troops in Afghanistan, Hur suggests that some members of a putative jury might “conclude that if Mr. Biden found the classified Afghanistan documents in the Virginia home, he forgot about them rather than willfully retaining them.” In other words, Biden’s forgetfulness was not pathological—it was merely the mundane operation of the human mind, which a jury would accept as normal and understandable.

This is surely right. It’s not just that the evidence related to the classified documents does not support any accusation that Biden deliberately withheld them from the archives. It’s also that it does not support the much more politically charged implication that the poor treatment of these documents is evidence of senility. Biden had these papers in his homes quite legitimately while he was vice-president. Some of them got shunted into the memory hole of an ordinary suburban garage. That he forgot about them is emphatically not evidence of “diminished faculties in advancing age.”

The plain fact is that memory is always somewhat hazy, at any age. Indeed, as the White House noted in its rebuttal to the report, Hur references other instances of imprecise recall. Biden’s counsel Patrick Moore had the job of sorting Biden’s archives and searching for potentially missing documents that Biden should have handed over. Moore found documents in a small closet in Biden’s office at the Penn Biden Center at the University of Pennsylvania. Hur reports that “When interviewed by FBI agents, Moore believed the small closet was initially locked and that a Penn Biden Center staff member provided a key to unlock it, but his memory was fuzzy on that point.” Equally, Hur reports of another of Biden’s lawyers, John McGrail, that his memory of certain events was inconsistent with contemporary written records but concedes sensibly that “McGrail’s memory of these events could well have faded over the course of more than six years.” Does this mean that Moore and McGrail had diminished faculties? Of course not—people forget things.

*

The politically explosive part of Hur’s report, however, relates to a much more concentrated period of time: what Biden identified in his press conference as a five-hour grilling by the special counsel’s team over two days on October 8 and 9, 2023. This was in the immediate aftermath of the shock of Hamas’s atrocious assault on civilians in Israel. As Biden put it in his press conference, “it was in the middle of handling an international crisis.” In its rebuttal, appended to Hur’s report, the White House says that “in the lead up to the interview, the President was conducting calls with heads of state, Cabinet members, members of Congress, and meeting repeatedly with his national security team.” If Biden’s mind was elsewhere during the interviews with Hur, most of the world would surely agree that that’s exactly where it should have been.

Hur’s account of this meeting is nonetheless worrying:

In his interview with our office, Mr. Biden’s memory was worse. He did not remember when he was vice president, forgetting on the first day of the interview when his term ended (“if it was 2013—when did I stop being Vice President?”), and forgetting on the second day of the interview when his term began (“in 2009, am I still Vice President?”). He did not remember, even within several years, when his son Beau died. And his memory appeared hazy when describing the Afghanistan debate that was once so important to him. Among other things, he mistakenly said he “had a real difference” of opinion with General Karl Eikenberry, when, in fact, Eikenberry was an ally whom Mr. Biden cited approvingly in his Thanksgiving memo to President Obama.

These lapses of memory are significant and they do provide a troubling glimpse of how Biden may sometimes function in private meetings in the White House. But Hur also performs a sleight-of-hand. He turns the evidence from these two meetings in October into a much more sweeping insinuation about Biden’s mental capacities by linking it back to his unremarkable amnesia about the storage of the documents. He does this by projecting himself into the minds of putative jury members who would see Biden “as a sympathetic, well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory.”

How does he reach this surmise? He tells us explicitly: “At trial, Mr. Biden would likely present himself to a jury, as he did during our interview of him” (my emphasis). What Hur does here is to fuse the events that would be the subject of such a trial—Biden’s failure to remember where some documents were stored, a failure Hur accepts as perfectly normal—with his own characterization of Biden’s demeanor at the two meetings in October. Thus the perfectly mundane imperfections of memory become part of an accusation of near-senility, the only evidence for which is in those two meetings on especially fraught days in October.

This is grossly unfair. Insofar as Hur has a legitimate concern with the operation of Biden’s memory, it relates to the actual subject of his investigation: the storage of the documents. He provides no evidence at all that there was anything remarkable about Biden’s forgetfulness in this regard. Instead of sticking to his brief, however, Hur then shapes a politically lethal phrase out of a judgment he is not qualified to make—the lawyer appointing himself both as a doctor making a cognitive assessment and as a dramatist inventing a scenario for how twelve members of an imaginary jury might perceive Biden’s imaginary appearance in a witness box. It would be naive to think that Hur was unaware of the potentially historic consequences of this leap from evidence to conjecture.

*

This unfairness creates in turn a natural reaction among Democrats. If Biden is being treated so badly, the decent thing is to defend him and to dismiss the whole story as a politically motivated farrago. This is a serious mistake. Hur’s commentary on Biden’s cognitive abilities may be irrelevant to the job he was supposed to be doing. But it is not, alas, irrelevant to a presidential election that could shape American history for decades to come. For even if Hur’s is a low blow, it is a punch that someone was always going to land. Biden’s age is a gaping vulnerability that the Democrats have pretended not to see.

The right seizes on and magnifies every gaffe that Biden makes, but the blunders are real and seem increasingly frequent. In the days before he mixed up Sisi and Andrés Manuel López Obrador, he also confused Helmut Kohl with Angela Merkel and François Mitterrand with Emmanuel Macron. Under the pressure of a vicious election campaign, these moments may well happen more often and attract more attention. Hur’s report feeds into a narrative that was already established—that Biden is losing it—and makes it unavoidable.

Four days before Biden’s disastrous press conference, Hage Geingob died in a hospital in Windhoek, the capital of Namibia. Geingob, who was eighty-two and the serving president of Namibia, was the only other octogenarian running a democracy. His death leaves Biden in a club of one. Biden really is exceptionally old for a working head of government. And there has been consistent polling evidence that this is one kind of exceptionalism that Americans don’t want to claim. As the New York Times’s chief political analyst Nate Cohn puts it, Biden’s age is “arguably the single most straightforward explanation” for why he is trailing Donald Trump. “It’s what voters are telling pollsters, whether in open-ended questioning about Mr. Biden or when specifically asked about his age, and they say it in overwhelming numbers.” Those numbers include a majority of Democrats.

It’s no good pointing out that Trump is almost as old and equally prone to verbal slips. It’s no good highlighting the undoubted truth that, while Biden’s language may sometimes be uncomfortably sloppy, Trump’s loose lips utter toxic lies and dangerous slurs. These things don’t change the facts that no one has ever run for a presidential term at the end of which he would be eighty-six, that Trump gets a free pass on almost everything, and that Biden, fairly or otherwise, is the lightning rod for deep generational discontents and widespread unhappiness at the persistence of an American gerontocracy. His age gives Biden an apolitical way to retire gracefully, standing by his considerable achievements in office while passing the problem of being too old to be president onto Trump.

Nikki Haley was probably not wrong when she suggested after Biden’s press conference that “the first party to retire its eighty-year-old candidate will win the White House.” But if Biden persists in running, there will in effect be only one candidate: Trump. He will be the Republican contender but he will also be, as the monster to be feared, the primary motivator for Democratic voters. The election will be a referendum not on the incumbent president but on his challenger. Since Biden is unable to shake off the perception that he is too old to be president, he cannot make his own case effectively. He will rely on the simple proposition that he is not Trump. In a deeply uncomfortable sense, Trump, having taken ownership of the Republicans, will own the Democrats too.

The post The Memory Hole appeared first on The New York Review of Books.

The Politics of Memory in the Italian Populist Radical Right – review

In The Politics of Memory in the Italian Populist Radical Right, Marianna Griffini examines Italy’s political landscape, following the roots of fascism through to their influence on contemporary politics. Skilfully dissecting nativism, immigration, colonialism and the profound impact of memory on Italian political identities, the book makes an important contribution to scholarship on political history and theory and memory studies, according to Georgios Samaras.

The Politics of Memory in the Italian Populist Radical Right: From Mare Nostrum to Mare Vostrum. Marianna Griffini. Routledge. 2023.

Marianna Griffini’s The Politics of Memory in the Italian Populist Radical Right stands as a thorough examination of Italy’s political landscape, weaving together historical threads and contemporary realities. The book provides a nuanced analysis that dissects the roots of Italian fascism and charts the trajectory of its influence on present-day politics, offering a solid exploration of the nation’s political memory.

Marianna Griffini’s The Politics of Memory in the Italian Populist Radical Right stands as a thorough examination of Italy’s political landscape, weaving together historical threads and contemporary realities. The book provides a nuanced analysis that dissects the roots of Italian fascism and charts the trajectory of its influence on present-day politics, offering a solid exploration of the nation’s political memory.

Griffini sets the stage for an exploration of how collective memory shapes political ideologies

The eight chapters form a cohesive narrative that progressively deepens the understanding of Italy’s political milieu. Chapter One serves as a poignant introduction, capturing the current state of the Italian radical right and framing the central theme of memory. Griffini sets the stage for an exploration of how collective memory shapes political ideologies, a theme that reverberates throughout the subsequent chapters.

Chapter Two delves into the concept of nativism, contextualising it within both the broader European framework and the specific nuances of Italian politics. This nuanced exploration lays the foundation for comprehending the intricate dance between nativism, populism and the enduring echoes of Italy’s fascist past. Chapter Three, clearly outlines the research methodologies, establishing the scholarly background underpinning the entire work.

Chapter Four posits the emergence of the nation-state and examines the impact of otherisation, offering a lens to comprehend the dynamics of Italian politics. Otherisation, as a concept, illuminates how politicians endeavour to portray certain societal groups as different, often excluding them from the national identity. In this chapter, the analysis effectively traces, in a historiographical manner, the gradual development of this phenomenon over several decades, establishing a connection to fascist movements.

Otherisation, as a concept, illuminates how politicians endeavour to portray certain societal groups as different, often excluding them from the national identity.

The book takes a pivotal turn in Chapter Five, addressing the weighty topic of immigration and the multifaceted challenges it poses. This chapter serves as a bridge, connecting historical narratives with contemporary realities, offering a comprehensive understanding of the role immigration plays in shaping political discourse.

Chapter Six unfolds a detailed analysis of colonialism and its impact on attitudes toward immigration. Griffini’s exploration of colonial pasts and their connection to collective memory, as presented in Chapter Seven, adds a further layer of historical depth, illustrating the enduring influence of historical legacies on present-day political ideologies. The theoretical approach of memory underscores the colonial exploitation of other cultures by Italy. Notably, Griffini highlights how memory could be approached from a different angle in order to humanise and confront Italy’s colonial past, instead of supressing it.

Griffini highlights how memory could be approached from a different angle in order to humanise and confront Italy’s colonial past, instead of supressing it.

The zenith of the book occurs in Chapter Eight, where Griffini articulates the central argument concerning the profound influence of memory on shaping political identities. This segment stands as the magnum opus of the analysis, persuasively contending that the historical omission of specific memories related to both embracing and challenging Italy’s colonial past serves as a catalyst for the resurgence of fascist attitudes. This provides a critical insight into Italy’s seemingly inescapable political patterns.

The historical omission of specific memories related to both embracing and challenging Italy’s colonial past serves as a catalyst for the resurgence of fascist attitudes.

The book not only navigates the complexities of Italian politics but also engages with theoretical debates, contributing valuable insights to the understanding of populism. By elucidating the links between emotionality and the radical right, Griffini demonstrates how political ideologies, when fused with emotional undercurrents, can yield extremist outcomes.

A noteworthy strength of the book is its emphasis on ethnocultural ideas and the notion of belonging to the nation, especially in the context of increased migration within the European Union. The examination of otherisation as a phenomenon serves as a profound analysis, unravelling how Italian voters perceive the intricate role of the nation and how this perception catalyses the rise of radical right movements.

While the discussion between colonial and political theory may initially challenge some readers, it ultimately contributes to the richness of the analysis. The book successfully navigates the fluid boundaries of these theories, illuminating historical concepts that persist in the shadows and continue to shape contemporary political landscapes. However, a clearer bridge between those two concepts would have been useful for readers who are not entirely familiar with all the technical terms explored in the book.

[The book] provides key findings that not only shed light on the surge of the radical right but also offer a template for understanding the intricate political dynamics in other European countries.

The Politics of Memory in the Italian Populist Radical Right emerges not only as an exploration of Italian politics in 2022 but as a timeless contribution to scholarly literature. It provides key findings that not only shed light on the surge of the radical right but also offer a template for understanding the intricate political dynamics in other European countries.

Griffini delves into Italy’s colonial past, shedding light on its historical neglect and the deliberate concealment of past atrocities. This collective memory has been influenced by the infiltration of fascist tendencies into contemporary Italian politics. While the rise of far-right parties was noticeable up until 2022, none matched the achievements of Meloni with her election that year. Griffini’s examination of Italy’s colonial history offers a partial explanation for the limited comprehension of the nation’s past, intricately intertwined with its fascist history.

While the rise of far-right parties was noticeable up until 2022, none matched the achievements of Meloni with her election that year

Also, the book’s refusal to indulge in unnecessary predictions is a testament to its commitment to historical rigor. Given the unpredictable nature of Italian politics, this decision aligns with the broader theme of acknowledging the complexity inherent in the nation’s political trajectory.

In conclusion, despite the potential challenge for some readers in navigating between colonial theory and the concept of memory, the book constitutes an important contribution to scholarship on political history and theory and memory studies. Further research in the field is important for a more profound understanding of the intricate political dynamics unfolding in other European countries, illuminating how the normalisation of the radical right often stems from historical complexities. This book is highly recommended for students exploring Italian politics in 2022 and academic scholars seeking familiarity with historical perspectives shaping the extremes of the political spectrum in Italy.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Alessia Pierdomenico on Shutterstock.

Memory and culture after 1989 in Central Europe

The years following the collapse of the socialist-Stalinist regimes of eastern Europe were not comfortable for the people of the GDR, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and many other countries. The economic arrangements of a centrally planned economy abruptly collapsed, and new market institutions were slow to emerge and often appeared indifferent to the needs of the citizens. The results of "shock therapy" were prolonged and severe for large segments of these post-socialist countries (Hilmar 6-8). Till Hilmar's Deserved: Economic Memories After the Fall of the Iron Curtain tries to make sense of the period -- and the ways in which it was remembered in following decades.

Here is how Hilmar defines his project:

I ask: how it is possible that people who underwent disruptive economic change perceive its outcomes in individual terms? A common answer is to say that we live in neoliberal societies that encourage people to put their self-interest first and to disregard others around them. People have become atomized and isolated, the argument goes, and they have unlearned what it means to be part of a community. They have forgotten what we owe each other. Yet something is not quite right about this diagnosis. It assumes that we live our lives today in a space that is somehow devoid of morality. It thereby misses a crucial fact: people are embedded in social relations, and they therefore articulate economic aspirations and experiences of a social dynamic. In this book, I daw on in-depth interviews with dozens of people who lived through disruptive economic change. Based on this research, I show that it is precisely the concern of what people owe each other -- the moral concern -- that drives how many people reason about economic outcomes. They perceive them, I demonstrate, through the lens of moral deservingness, judgments of economic worth that they pass on each other. (3)

The central topic, then, is how individual people remember and make sense of economic changes they have experienced. Hilmar places a locally embodied sense of justice at the center of the work of meaning-making that he explores in interviews with these ordinary people affected by a society-wide earthquake.

Hilmar's method is an especially interesting one. He compares two national cases, Czechoslovakia and the GDR, and he bases his research on focused interviews with 67 residents in the two countries during the transition. The respondents are drawn from two categories of skilled workers, engineers and healthcare workers. His approach "enabled a focus on people's work biography and their sense of change in social relations" (15).

His central theoretical tool is the idea of a moral framework against which people in specific times and places interpret and locate their memories. "The memory of ruptures is guided by concerns about social inclusion. What makes a person feel that he or she is a worthy member of society? In our contemporary world, the answer to this question has a lot to do with economics" (17). Or in other words, Hilmar proposes that people understand their own fates and those of others around them in terms of "deserving-ness" -- deserving their successes and deserving their failures. And Hilmar connects this scheme of judgment of "deserving" to a more basic idea of "social inclusion": the person is "included" when she conforms to existing standards and expectations of "deserving" behavior. "A person's sense of accomplishment and confidence -- in the professional, in the civic, as well as in the private realms -- are all part of a social and normative ensemble in which the grounds for acclaim are social and never just individual" (18). And he connects this view of the social and economic world to the ideas of "moral economy" offered by E.P. Thompson and Karl Polanyi. A period of inequality and suffering for segments of the population is perceived as endurable or unendurable, depending on how it fits into the prevailing definitions of legitimacy embodied in the historically specific moral economy of different segments of society. In the Czech and German cases Hilmar considers, social inclusion is expressed as having a productive role in socialism -- i.e., having a job (39), and the workplace provided the locus for many of the social relationships within which individuals located themselves.

The central empirical work of the project involves roughly seventy interviews of skilled workers in the two countries: engineers and healthcare workers. Biographies shed light on large change; and they also show how individual participants structured and interpreted their r memories of the past in strikingly different terms. This is where Hilmar makes the strongest case for the theoretical ideas outlined above about memory and moral frameworks. He sheds a great deal of light on how individuals in both countries experienced their professional careers before 1989, and how things changed afterwards. And he finds that "job loss", which was both epidemic and devastating in both countries following the collapse of socialism, was a key challenge to individuals' sense of self and their judgments about the legitimacy of the post-socialist economic and political arrangements. Privatization of state-owned companies is regarded in almost all interviews as a negative process, aimed at private capture of social wealth and carried out in ways that disregarded the interests of ordinary workers. And the inequalities that emerged in the post-1989 world were often regarded as profoundly illegitimate, based on privileged access rather than. merit or contribution:

People grew skeptical of the idea that above-average incomes and wealth could in fact be attained through hard work. Instead they began to associate it with nepotism and dishonesty. On these grounds, researchers posit that the principle of egalitarianism returned as the dominant justice belief after the bout of enthusiasm for market society. (94)

This is where the idea of "deservingness" comes in. Did X get the high-paid supervisor job because he or she "earned" it through superior skill and achievement, or through connections? Did Y make a fortune by purchasing a state-owned shoe factory for a low price and selling to a larger corporation at a high price because he or she is a brilliant deal maker, or because of political connections on both ends of the transactions?

The discussion of social relations, informal relations, and trust in post-socialist societies is also very interesting. As Delmar puts the point, "you can't get anything done without the right friends" (118). And social relationships require trust -- trust that others will live up to expectations and promises, that they will honor their obligations to oneself. Without trust, it is impossible to form informal practices of collaboration and cooperation. And crucially: how much trust is possible in a purely market society, if participants are motivated solely by their own economic interests? And what about trust in institutions -- either newly private business firms or government agencies and promises? How can a worker trust her employer not to downsize for the sake of greater profits? How can a citizen trust the state once the criminal actions of Stasi were revealed (138)? What was involved in recreating a basis for trust in institutions after the collapse of socialism?

Through these interviews and interpretations the book provides a very insightful analysis of how judgments of justice and legitimacy exist as systems of interpretation of experience for different groups, and how different those systems sometimes are for co-existing groups of individuals facing very different circumstances. And the concrete work of interview and interpretation across the Czech and German cases well illustrates both the specificity of these "moral frameworks" and some of the ways in which sociologists can investigate them. The book is original, illuminating, and consistently insightful, and it shows a deep acquaintance with the literature on memory and social identity. As such Deserved is a highly valuable contribution to cultural sociology.

(It is interesting to recall Martin Whyte's discussion of generational differences in China about the legitimacy of inequalities in post-Mao China. The Mao generation is not inclined to excuse growing inequalities, whereas the next several generations were willing to accept the legitimacy of inequalities if they derived from merit rather than position and corrupt influence (link). This case aligns nicely with Hilmar's subject matter.)

The Monk, the Memorist, the Mushroom and the MRI

Discover how we create and store ideas, and how modern neuroscience process 16th century theories on memory.

Migration, Memory and Identity

Part of the Humanities & Identities Lunchtime Seminar Series

Whither Death?

Helen Swift and Jessica Goodman discuss the one day conference 'Whither Death?' Helen Swift (Associate Professor of Medieval French) and Jessica Goodman (Associate Professor of French) discuss the one day conference 'Whither Death?', discussing memory and life-writing.