Marx

Limitations of Hobsbawm's historical writing

A defining component of Eric Hobsbawm’s historical writings is the quartet of “Age” books: Age of Revolution, Age of Capital, Age of Empire, and Age of Extremes. These are synthetic works, offering a narrative of the long nineteenth century and the short twentieth century. They give primary attention to developments pertaining to economic, political, and social change in Britain, Europe, and North America, with occasional commentary on the rest of the world (Asia, Africa, and South America). Perhaps the most interesting of these is the first of them, Age of Revolution. Hobsbawm’s central interest – the central story he tries to tell – is the unfolding of the “dual revolutions” – the industrial revolution and the French Revolution – and the consequences these revolutions had for the lives, political identities, and historical agency and activism of working people. These revolutions formed “modernity”, whether in technology, in political forms, or in conditions of material life. And they gave rise to the central social formations (“great classes”) and political ideologies (nationalism, socialism, fascism) that continue to orient our world today.

These books are highly detailed. But we should observe that they are almost entirely grounded in secondary scholarship – Hobsbawm seems to have read almost everything written on this two-century period, and has undertaken to crystallize the main currents of research and interpretation into a reasonably coherent and connected narrative. But very little of the Age of Revolution depends upon Hobsbawm’s own primary research as a social historian. And though the tone of the narrative is even-handed and calm, the impression emerges over the 350-plus pages of the book that it is very deeply informed by the narrative of the Communist ManifestoConditions of the Working Class in England. This is a coherent narrative; but there are other stories that might be told of the nineteenth century, and other organizing themes that might be the hinges of the story.

Hobsbawm’s own primary scholarship focused on “indigenous” class movements and uprising, largely in England. He was a labor historian, and he was interested in uncovering documents and narratives that shed light on the ways that ordinary working people in the 18th and 19th centuries lived, how they conceived of the social relations around them, and how they rebelled. Key works here include Labour’s Turning Point 1880-1900 (1948), Primitive Rebels: Studies in archaic forms of social movements in the 19th and 20th centuries (1959), Labouring Men: Studies in the History of Labour (1964), and Captain Swing (1969; co-authored with George Rudé). The recurring theme of these earlier works was the topic of resistance and popular identities among “working people”. In “Captain Swing: A Retrospect” (link) Adrian Randall describes Hobsbawm’s orientation in these terms:

Hobsbawm’s earlier work, mainly concentrated on the labour history of later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was steeped in the well- established Marxist interpretation of economic and social history which saw the years from the later eighteenth century as marking an industrial revolution which had transformed economic, and thence social and political, relations into a more clearly class-divided form. The displacement of a peasantry and the degradation of agricultural labourers formed part of that narrative. (Randall 2009: 421)

But even here Hobsbawm’s role seems to be synthetic rather than primary. The division of labor in Captain Swing seems to divide sharply between Rudé’s primary scholarship on eighteenth-century uprisings (Randall 2009:421) and Hobsbawm’s synthetic historical imagination, guided by Marx’s conceptualization of history. Here too, then, Hobsbawm works as a theoretically-minded historical narrativist rather than as a primary historical researcher.

Might we say, then, that we need less from a historian than what Hobsbawm gives us? Hobsbawm paints a consistent, detailed picture of the evolution of social unrest. But it is fundamentally just an extensive interpretation based on a reading of secondary sources, and it may even be a caricature – certain features may be over-drawn and others minimized, in order to make the coherent and consistent Marxist story plain. But we don’t want our knowledge of history to be “pre-digested” according to a prior plan; we want a reasonable, evidence-based account that is open to contingency, unexpected developments, and details that do not fit the model.

In my mind I contrast Hobsbawm’s Ages books with Jill Lepore’s These Truths, which provides an account of the history of the United States that is not wedded to any particular trope. Instead, Lepore seeks to document and discuss the many themes that enter into US history, without bending the edges to make the facts fit the frame. And I think of more regional and local historians, such as William Sewell (Work and Revolution in France), whose analysis of the “working-class consciousness” of working people of Marseille breaks many stereotypes of the Marxist hymnal. And Sewell’s work, unlike Hobsbawm’s, is deeply grounded in his own research on primary documents and sources. Here is how Lynn Hunt describes Sewell’s primary research in Work and Revolution (link):

Sewell’s sources are eclectic: they range from a philosophical tract by Diderot to the statutes of mutual-aid societies, from artisanal and working-class newspapers to quasi-official reports on the conditions of the working poor, from intellectual tracts on socialism to workers’ poetry. All these comprise “a set of interrelated texts that demand close reading and careful exegesis” (11-12). Sewell rereads and reinterprets these texts with an eye for their linguistic and historical logic. The “socialist vision of labor” was a logical development of certain fundamental Enlightenment concepts, but that logic was pushed forward not so much by intellectual as by social and political developments, in particular, by the revolutionary “bursts” of 1830-34, 1839-40, and 1848-51 (278). In attempting to explicate this “dialectical logic,” Sewell synthesizes an extensive published literature on French labor, and he effectively underlines the importance of paying very close attention to what people in the past said, sometimes indirectly, about what they were doing.

Perhaps this suggests that we need another category of historical misrepresentation beyond the two offered by Andrus Pork (link). In addition to “direct lies” and “blank-page lies”, we need “interpretations of history cut to order by an antecedent interpretation of history”.

Fresh audio product: political economy—the feline angle; understanding capitalism to smash it

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

November 30, 2023 Leigh Claire La Berge, author of Marx for Cats, on political economy and the human–feline relationship • Michael Zweig, author of Class, Race, and Gender, on understanding capitalism in order to transform it

The Labour Theory of Value is Correct and Important

I’m returning to the Labour Theory of Value (LTV) after writing a series of posts about it here, here, here, here, and here.

Writers on Marx often claim that the LTV isn’t necessary to understand his story about capitalism, the nature of exploitation, etc. A recent example is found in this blog post by Professor Liam Kofi Bright at the London School of Economics. I think people say this because the LTV is supposed to have been refuted, and they don’t want to damn the rest of Marx’s theory alongside it.

I believe that (i) the LTV is indispensable to Marx’s story and (ii) this shouldn’t worry those who believe his story, because the theory is correct. The refutation rests on a false assumption.

What is the Labour Theory of Value?

By the LTV here I mean the theory that the exchange value of a commodity — any good or service — is determined by the amount of average labour time that goes into making it and making any inputs into its production (for example, extracting the raw materials that it is made from, or building the tools and machinery used in making it). Call this its “labour content”.

Exchange value is something like a long-term average of price, not the price at any given moment. Bright gives an example: “the price of shovels goes up when a snow-storm is anticipated even though the anticipation of a snow storm has done nothing to change the socially necessary labour time involved in producing those shovels”. The LTV predicts only that the price of snow shovels will, in the long run, gravitate around a value determined by the labour content, not that it won’t fluctuate in the short-term due to changes in demand.

Why Is It Needed?

The LTV is very important for Marx’s story of exploitation, I think. G.A. Cohen argued that it isn’t, but his argument is invalid in my opinion (see here and here).

Cohen and other “Analytic Marxists” essentially argue that we can reconcile much of Marx’s analysis of capitalism with the neoclassical theory of value. I disagree, because I believe that the notion of exploitation is fundamental to Marx’s analysis, and exploitation must mean here something simple and non-normative, e.g. that workers receive less in wages than the value of their labour.

This is easy to calculate on the LTV. Suppose that I, a capitalist, pay a group of workers wages worth 1000 hours of average labour-time and supply 200 hours’ worth of fixed capital (tools, raw materials, etc.). If I sell the resulting products for 1400 hours’ worth of money, then I have made a profit of 200/1400 (around 14%). But then the commodity must, by the LTV, have a labour content of 1400 hours. Since I only spent 1200 hours’ worth on costs, where did the extra 200 hours come from?

The price I paid for the fixed capital must, on average, be proportionate to its labour value, since this is true of all commodities according to the LTV. So I must have underpaid for the workers’ labour. They must have supplied 1200 hours of labour, even though I only paid them wages worth 1000 hours.

But isn’t labour also a commodity? Shouldn’t it, therefore, also be subject to the LTV? Here Marx’s answer is complex: the workers do not sell their labour to the capitalist; they sell their labour power. Labour power is the capacity to work for as many hours as physically possible given the “input” of a certain wage. Since my workers could work for 1200 hours while consuming wages worth 1000 hours, buying their labour power allowed me to extract value from them. This is fundamentally how capitalism works, on Marx’s theory.

It raises many questions. For one thing: why don’t workers sell their labour instead of their labour power? Everyone else in the economy demands equivalent value in exchange for what they give up: if the workers give up 1200 hours, shouldn’t they demand 1200 hours? A naive Marxist will reply that the workers under capitalism are too oppressed to make any demands, but the question is why. You might have thought, after all, that competition among capitalists would bid up wages for a limited supply of labour.

Marx’s answer to this involves a complex story about the distribution of power under capitalism, the dynamics of the population of workers and employment cycles, the theory of crisis, etc. The problem with this is that, in my opinion, the more complex a story is, the more limited its application. If the conditions of capitalism require a specific arrangement involving the legal power of workers, a certain population dynamic, a particular pattern of business cycles, etc., then this muddies the definition of capitalism, and working out whether Marx’s analysis applies to a given situation becomes a very vague matter.

No Exploitation Without LTV

What is clear, however, is that the LTV is crucial to the story. Cohen suggests, by contrast, that we can define exploitation using a neoclassical (or, he says, any other) theory of value. Just say that the workers produce the whole of the product but are paid only some of its value in wages.

But, in the first place, it isn’t clear that the workers are in any way disadvantaged by this, if we aren’t sure that labour is the sole source of value. The capitalists can say that while the workers produced the product, the capitalists supplied the capital necessary for production and are thus entitled to some of its value. The landlords can likewise say that they, the landlords, supplied the land on which the production took place, so they are also entitled to some of the value. The value of the product, on a simple textbook model, will be a function of the factors that went into it — land, labour, capital — so splitting the proceeds among the workers, capitalist, and landlord might well count as giving back everyone the value they supplied.

Secondly, on a neoclassical theory it can be argued that the workers are paid the full value of the product, even if e.g. the product sells for £1200 net of non-labour costs and the workers are paid £1000. That is because the workers were paid before or during the period of production, but the product was only sold at the end of the period. The rate of time-discounting enters in here, and if it is 16.6% over the given period then the workers can be said to have received the full (present discounted) value of their product. The capitalist reaps the rewards of patience, and there is no exploitation.

John Roemer also attempts to square Marx with a neoclassical theory of value, and ends up concluding that Marxists shouldn’t be interested in exploitation.

Why Is LTV Correct?

The neoclassical theory, however, is largely devoid of empirical support. The most sophisticated version of the neoclassical theory of capital involves intertemporal general equilibrium models, whose disconnection from any empirical evidence was demonstrated long ago by Dan Hausman.

The LTV, by contrast, is very well-supported empirically, as has been shown by Anwar Shaikh, Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell, Lefteris Tsoulfidis and Thanasis Maniatis, Dave Zachariah, and many others.

The key to confirming it empirically is to treat it as what it is: a theory of a statistical equilibrium. Prices can be all over the place, but they will on average tend to be proportional to labour content, although any given price can be much higher or lower than this. Such a statistical correlation calls out for a causal mechanism to explain it, and a mechanism is suggested by the mathematicians Emmanuel Farjoun and Moshé Machover in Laws of Chaos and by a team of engineers and physicists in Classical Econophysics (ch.9).

What they do is use probabilistic methods to study value as an emergent statistical property of a very random system operating under certain constraints, which looks much more like a real economy than the stable solutions of neoclassical economics (human choices, for example, are better modelled by random noise than they are by rational optimisation).

The truth of the LTV as a matter of statistical averages was also recognised by Joan Robinson, who wrote, in Economic Philosophy (1962) that in manufacturing industry “differences in prices are more or less proportional to labour cost, and on the other hand they are not exactly proportional”, for a variety of reasons. “What”, she asked, “is all the fuss about?” The LTV holds up very well as a general predictor of relative prices, so why has there been so much controversy about it?

The Transformation Non-Problem

Marx’s theory of exploitation is sometimes rejected on account of something called the “transformation problem”, which arises from the LTV along with the assumption that competition should drive different industries to have the same rate of profit even though they use differing proportions of labour. The idea is that if different rates of profit are available in different industries, capitalists will move their investments out of the lower-profit ones and into the higher-profit ones until all profit rates are roughly equal. This will lead to prices no longer matching labour content.

Farjoun and Machover have explained that while scholars took the LTV to be the culprit in the transformation problem, there is in fact no good reason to accept the assumption of a uniform rate of profit, equalized through competition. As they put it in a later work: “the very mechanism of equalization — competition and capital reallocation — also creates irreducible motion of firms away from a state in which all profit rates equal the average”. It is true that self-interested capitalists will move out of lower-profit industries into higher-profit industries, but as a result prices and quantities will be constantly changing across the economy and profits will end up forming a fairly random distribution around a certain average.

Exploitation and the LTV

Where this leaves exploitation is interesting. Farjoun and Machover do not take on Marx’s theory of “labour power”, with all its heavy commitments. But this then raises the question of why, if prices generally correspond to labour content, the same shouldn’t go for labour. Why isn’t the price of an hour’s labour, on average, a wage worth one hour’s labour?

If it were, the average profit rate would be zero. By the time the capitalist had paid all the workers for their hours of labour and all the sellers of all non-labour inputs for the hours of labour embodied in those inputs, she would have paid the full value of the product sold and have nothing left for profit. Again, all of this is on average. Some capitalists would earn positive profits and others would lose money, but it would all average out to zero, and capitalism would be unviable in the long run.

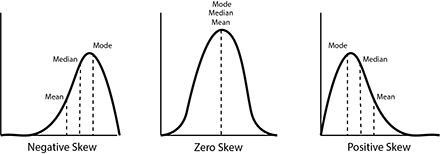

To see why labour is not paid proportionately to its value, on average, we can compare it to another commodity in this probabilistic theory of prices. The price of an ordinary commodity-type will form a normal distribution around an average determined by labour content. Some commodities of that type will be sold for much more than their value, others will be sold for much less, but the bulk will be sold for something pretty close to their value.

For labour, however, there is another constraint. Labour cannot be sold for too little, otherwise workers will starve. This means that the distribution around value of labour prices (wages), will have a positive skew: the curve will be squashed up against the lower bound. As this post very helpfully explains, in a distribution with a positive skew, the median value (in this case, the hourly wage that most people are paid) will be lower than the mean (the actual labour-value of labour).

This is an interesting result, because it suggests that it is a fundamental feature of capitalism, quite broadly defined, that it involves exploitation in the sense that workers are systematically paid less than the value of their labour. Such a consequence is simply the statistical outcome of a system in which prices are determined in exchange and a significant proportion of the population need to sell their labour in order to survive.

Some workers, of course, are paid more than their value. If they were paid less — that is, if worker incomes were more equal—then the distribution would be squashed less hard against its lower bound and the median would move closer to the mean. More workers would be paid something close to the actual value of their labour.

If you want to know whether you’re part of the problem, Farjoun, Machover, and Zachariah estimate (ch.6) that the proportion of workers earning more than the value of their labour in wages is something like 10%. So that’s you, if you’re in something like the top 10% of earners. In the UK this is anyone on a yearly salary of around £65,000 or upwards. You could reduce the rate of exploitation by taking a pay cut. But eliminating exploitation would require a completely different system.

The Labour Theory of Value is Correct and Important was originally published in Genus Specious on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Moses Finley's persecution by McCarthyism

MI Finley (1912-1986) played a transformative role in the development of studies of the ancient world in the 1960s through the 1980s. He contributed to a reorientation of the field away from purely textual and philological sources to broad application of contemporary social science frameworks to the ancient world. His book The Ancient Economy (1973) was especially influential.

Finley was born in the United States, but most of his academic career unfolded in Britain. The reasons for this "brain drain" are peculiarly America. Like many other Americans -- screenwriters, actors, directors, government officials, and academics -- Finley became enmeshed in the period of unhinged political repression known as McCarthyism. Finley was named as a member of the Communist Party of the United States by fellow academic Karl Wittfogel in his own sworn testimony to the McCarran Committee (United States Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security). (Pat McCarran (D-NEV) was also the primary sponsor of the Subversive Activities Control Act (1950), which provided for mandatory registration of members of the Communist Party and created the legal possibility of "emergency detention" of Communists. Police state institutions!) When Finley was called to testify under oath to the committee, he declined to answer any questions based on his Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination. He was subsequently fired by Rutgers University for his refusal to answer the committee's questions. (Daniel Tompkins' essay "Moses Finkelstein and the American Scene: The Political Formation of Moses Finley, 1932-1955" provides some valuable information about the first half of Finley's career until he departed the United States; link.)

It should be noted that one's Fifth Amendment rights do not allow the witness to pick and choose which questions he or she is willing to answer. Many of the witnesses who took the Fifth during this period were fully willing to discuss their own activities but were not willing to name associates -- for example, Case Western Reserve professor Marcus Singer. Here is a brief summary of Singer's case taken from his New York Times obituary (October 11, 1994).

In 1953, when he was on the Cornell University faculty, Dr. Singer was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and questioned about his political affiliations. He admitted having been a Communist until 1948, although he said he had never held a party card. He refused to name Communists he had known while teaching at Harvard, from 1942 to 1951, on grounds of "honor and conscience" and invoked the protection of the Fifth Amendment.

In 1956, he was convicted of contempt of Congress, fined $100 and given a three-month suspended sentence in Federal District Court in Washington, which ruled that he had waived the Fifth Amendment's protection. In 1957 the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit set aside the conviction, saying its ruling was required by a Supreme Court decision in a similar case. The court sent the case back to Federal District Court with instructions to enter a judgment of not guilty.

In hindsight the willing participation of university presidents, law professors, and other faculty in the effort to exclude Communists or former Communists from faculty positions, and to fire professors who chose to plead the fifth amendment rather than provide testimony to the various congressional committees about their associates seems to reflect an almost incredible level of hysteria and paranoia. Ellen Schrecker documents the compliant actions of many administrators, trustees, and fellow faculty members (link). This was a betrayal of the principles of academic and personal freedom. One does not need to be an advocate of the Communist Party in order to defend a strong principle of academic freedom for all professors; and yet administrators and faculty at many leading universities were eager to find ways of supporting these anti-Communist measures. Schrecker quotes an official statement of the AAU in 1953 that provided grounds for firing faculty for membership in the Communist Party and for refusal to testify about their activities (link):

The professor owes his colleagues in the university complete candor and perfect integrity, precluding any kind of clandestine or conspiratorial activities. He owes equal candor to the public. If he is called upon to answer for his convictions, it is his duty as a citizen to speak out. It is even more his duty as a professor. Refusal to do so, on whatever legal grounds, cannot fail to reflect upon a profession that claims for itself the fullest freedom to speak and the maximum protection of that freedom available in our society. In this respect, invocation of the Fifth Amendment places upon a professor a heavy burden of proof of his fitness to hold a teaching position and lays upon his university an obligation to reexamine his qualifications for membership in its society. (325)

The AAUP eventually issued a statement condemning firing of professors for these reasons in 1956; but the damage was done.

But what about MI Finley? Was he a member of the CP-USA? And did this membership influence his thinking, teaching, and writing? Was he unsuitable to serve as a professor at an American university? F.S. Naiden answers the first question unequivocally: "Incontrovertible evidence now shows that Moses Finkelstein, as he was then named, joined the Party in 1937–8. The Party official who enrolled him, Emily Randolph Grace, reported this information in a biographical note she wrote about Finley in order to prepare for an international conference in 1960" (link). And Naiden suggests that his membership continued through the mid-1940s.

Let's take Naiden's assessment as accurate; so what? Should Finley's membership in the 1930s be viewed as basis for disqualification as a professor fifteen years later? Here the answer seems clear: Finley's choices in the 1930s reflected his political and social convictions, his ideas and thoughts, and should fairly be seen as falling within his rights of freedom of thought, speech, and association. If his political ideas led him to commit substantive violations of the law, of course it would be legitimate to charge him under the relevant law; but there is no suggestion that this was the case. So Finley's persecution in 1953 -- along with the dozens of other faculty members who were fired from US universities for the same reason -- is just that: persecution based on his thoughts and convictions.

And what about his teaching? Did his previous membership in the Communist Party interfere with his professional responsibilities to his students or to the academic standards of his discipline? Again, the answer appears to be unequivocal. Finley, like the great majority of other professors dismissed for their Communist beliefs, appeared to make a strong separation between his personal political beliefs and the content of his teaching. He did not use the classroom to indoctrinate his students. And his activism in the 1930s -- organizing, leafletting, efforts to persuade others -- was clearly separated from his academic performance. (He had not even completed his PhD during the prime years of his membership in the Communist Party.) So any unbiased observer from Mars would judge that Finley was a fully ethical academic.

Finally, what about his research and writing? Did his membership in the Communist Party distort his scholarship? Did it interfere with his ethical standards of honesty and evidence-based historical research? Again, by the evidence of his writing, this charge too seems wholly unsupportable. Finley was a superb scholar, and his research is grounded in a reasonable and extensive marshaling of evidence about the social and economic realities of the ancient world. Finley was not a communist hack; he was not a dogmatic ideologue; rather, he was a dedicated and evidence-driven scholar -- with innovative theoretical and methodological ideas.

It is especially interesting to read Finley's short essay on the trial of Socrates in the context of his political persecution in the United States in 1953 (Socrates on Trial, first published in slightly different form in Aspects of Antiquity in 1960). Though there is an obvious parallel between the trial of Socrates and the encounter between Finley and the United States Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security -- in each case the accused is brought to legal process based on his thoughts and criticisms of the society in which he lives -- there is no indication in this text that Finley wishes to draw out this comparison. Instead, most of his essay focuses on the point that much of the trial of Socrates has been mythologized for political purposes -- to attack direct democracy and the tyranny of the majority. Plato's text is a work of literature, not a transcription of the details of the accusations and the responses of Socrates.

Paradoxically, it is not what Socrates said that is so momentous, but what Meletus and Anytus and Lycon said, what they thought, and what they feared. Who were these men to initiate so vital an action? Unfortunately, little is known about Meletus and Lycon, but Anytus was a prominent patriot and statesman. His participation indicates that the prosecution was carefully thought through, not merely a frivolous or petty persecution.

And Finley attempts to understand the thinking of the jurors themselves by placing the trial in the context of the massive Athenian trauma of the Peloponnesian War and two devastating plagues:

One noteworthy fact in their lives was Athens had been engaged in a bloody war with Sparta, the Peloponnesian War, which began in 431 B.C. and did not end (though it was interrupted by periods of uneasy peace) until 404, five years before the trial. The greatest power in the Greek world, Athens led an exceptional empire, prosperous, and proud -- proud of its position, of its culture, and, above all, of its democratic system. But by 404 everything was gone: the empire, the glory, and the democracy. In their place stood a Spartan garrison and a dictatorship (which came to be known as the Thirty Tyrants). The psychological blow was incalculable, and there was not a man on the jury in 399 who could have forgotten it.

So Finley offers a historically dispassionate reading of the trial of Socrates. But we might draw out the essential parallel between the two cases anyway. We might say that Finley, like Socrates, was attacked because he "denied the gods of the city" -- in Finley's case, he challenged the unquestioned moral superiority of capitalism over socialism; and because he threatened to "corrupt the youth" -- to teach through his classroom and his example an unwholesome inclination to "communism". Might we say that the "crimes" of Socrates and Finley were similar after all, in the minds of their persecutors: they were too independent-minded and too critical of their society for the good of society?

I.F. Stone's Trial of Socrates offers a fascinating perspective on Socrates that is relevant to these connections to Finley; and in fact, Stone suggested to Finley that he should write a memoir of his experience (Tompkins (link) p. 5). In Trial of Socrates he writes: "Was the condemnation of Socrates a unique case? Or was he only the most famous victim in a wave of persecutions aimed at irreligious philosophers? ... Two distinguished scholars ... have put forward the view that fifth-century Athens, though often called the Age of the Greek Enlightenment, was also ... the scene of a general witch-hunt against freethinkers." The same words could apply to MI Finley and the dozens of other faculty members who lost their careers to McCarthyism, and to the regrettable failure of liberal democracy in those decades of ideological warfare against critics of capitalism.

Marxism and British historiography

It is noteworthy that some of the very best historical research and writing of the 1930s through 1970s in Britain was carried out by a group of Marxist historians, including E.P. Thompson, Maurice Dobb, Rodney Hilton, Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm, and a few others. Many belonged to the British Communist Party and were committed to the idea that only sweeping revolution of economy and politics could bring to an end the exploitation and misery of nineteenth- and twentieth-century capitalism. These historians did not align with the democratic socialists of the Fabian and Labour varieties (link), and the chief demarcation line had to do with the feasibility of gradual reform of advanced market economies. These were gifted and rigorous historians with a particular set of ideological commitments (link).

All of these historians researched some aspect or other of the history of "capitalism", an effort that required dispassionate and objective inquiry and assessment of the facts. Equally, all of them embraced a view of capitalism and a stylized history of capitalism that derived from Marx's writings -- especially Capital and the scattered writings defining the theory of historical materialism. Third, all of them had an ideological apple to peel (as a Dutch friend of mine used to say): they took the view that exploitation and misery were so intimately bound up in the defining institutions of capitalism that only wholesale revolution could root them out. And finally, most of them were politically committed to a party and a movement -- the Communist Party -- which itself made harsh demands on the thinking and writing of its adherents. The "party line" was not merely a form of discipline, it was an expression of loyalty to the cause of communism. And since Soviet communism dominated throughout the period from the 1920s to the 1970s, the party line was almost always "Stalinist" in the most dogmatic sense of the term. So the difficult question arises: how is it possible to reconcile a commitment to "honest history" with a commitment to Marxism and revolution?

Harvey Kaye's British Marxist Historians provides a detailed treatment of many of these historians, including Dobb, Hilton, Hill, Thompson, and Hobsbawm. Kaye fully recognizes the dual nature of the thinking of these historians: "I consider their work to be of scholarly and political consequence" (x). Kaye evidently believes that the scholarly and political commitments of these historians are in no way in conflict. But this is an assumption that must be examined carefully.

Kaye's book can be read as an effort to establish a careful geography of Marxist theoretical ideas about the development of capitalism and how those ideas were both used and transformed in the hands of these historians. His account of Dobb offers a detailed account of Dobb's view of a "non-economistic" historical treatment of capitalism, and he expends a great deal of effort towards identifying the key criticisms offered of Dobb's views by Paul Sweezy, Rodney Hilton, Robert Brenner, Perry Anderson, and others. The chapter can be read as a meticulous dissection of the definition of key ideas ("mode of production", "relations of production", "feudalism", "class conflict", ...) and the theoretical use that these various Marx-inspired historians make of these ideas to explicate "capitalist development" and the notion of "transition from feudalism" in its various historical settings. Most compelling is Kaye's treatment of E.P. Thompson's historical and theoretical writings. He makes it clear that Thompson provides a highly original contribution to the idea of "class determination" through his insistence on the dynamic nature of the formation of consciousness and experience in the men and women of the British laboring classes.

Kaye makes clear in his treatment of each of these historians that their research never took the form of a dogmatic spelling-out of ideas presented in Marx's writings, but rather a much more rigorous effort to make sense of the historical record of feudalism, the English Revolution, the early development of capitalist property relations, and the like. These were not Comintern hacks; they did not treat Marxism as a more-or-less complete theory of history, but rather as a set of promising insights and suggestions about historical processes that demand detailed investigation and analysis. And none of the books of these historians that Kaye discusses can be described as "orthodox Comintern interpretations" of historical circumstances. Kaye quotes Christopher Hill (102): "A great deal of Marxist discussion went on in Oxford in the early thirties. Marxism seemed to me (and many others) to make better sense of the world situation than anything else, just as it seemed to make better sense of seventeenth-century English history." And later in this chapter he quotes Hobsbawm (129): "An advantage of our Marxism -- we owe it largely to Hill ... was never to reduce history to a simple economic or 'class interest' determinism, or to devalue politics and ideology." These comments seem to point the way to partial resolution of the apparent conflict between political commitments and historical integrity: Marx's writings about capitalism, class, and historical materialism constitute something like a research programme or analytical framework for these historians, without eliminating the need for historical rigor and objectivity in searching out evidence concerning the details of historical development (in England, in France, or in Japan).

If we wanted to assess the possible distortions of historical selection and analysis created by party commitments with regard to historical writing and inference, one natural place to look would be at the selection of topics for research. Are there topics in British history that are especially relevant to the ideological concerns of the Communist Party in the 1940s and 1950s, and did the British Marxist historians stay away from those topics? Kaye remarks on Hobsbawm's own assessment of the role the party line played in defining issues and positions for the British Marxist historians: very little, according to Hobsbawm (15). He quotes Hobsbawm: "There was no 'party line' on most of British history,' at least as far as they were aware at the time." So we can reasonably ask: when these historians treat "politically sensitive" topics, do the analyses they offer seem to reflect ideological distortions?

Kaye notes that one topic that should be of interest to Marxist historians is the history of the labor movement in Britain. "The 'modern' historians of the Group were naturally most anxious to pursue and make known the history of the British labour movement and, no doubt, were encouraged in their efforts by the British Communist Party. And yet this was the one field in which constraint was felt in relation to the Party. As Hobsbawm has stated on a number of occasions, there were problems in pursuing twentieth-century labour history because it necessarily involved critical consideration of the Party's own activities" (12). Kaye also quotes from an interview Hobsbawm offered in 1978:

[Hobsbawm] acknowledges that he took up nineteenth-century history because when "I became a labour historian you couldn't really be an orthodox Communist and write publicly about, say, the period when the Communist Party was active because there was an orthodox belief that everything had changed in 1920 with the foundation of the C. P. Well I didn't believe it had, but it would have been impolite, as well as probably unwise, to say so in public". (134)

This passage makes it clear that Hobsbawm avoided twentieth-century British labor history precisely because the party line was in conflict with the historical realities as Hobsbawm saw them. So Hobsbawm refrained from writing about this period.

So a preliminary assessment is perhaps possible. When these Marxist historians went to work on a given historical topic, they exercised rigor and care in their assessments of the past; they enacted fidelity to the standards of honesty we would wish that historians universally embrace. And indeed, the historical work done by these historians does indeed conform to high standards of honesty and independence of mind -- even as the research focus on "capitalism" is framed in terms of Marxist concepts. But the example of Hobsbawm's statements about twentieth-century labor history imply that certain topics were taboo, precisely because independence of analysis would run counter to the party line. (Kaye also suggests that Hobsbawm's continuing adherence to the 'base-superstructure' model derived from his deference to the orthodox Party line on the nature of the mode of production; 135.)

But we can also ask an even more fundamental question: did the historians of this group take any public notice of the crimes of Stalinist USSR -- the Holodomor, the terror, the show trials, the Gulag? Or was explicit condemnation of systemic actions like the Holodomor or the Gulag too much of a repudiation of the Communist Party for these historians to accept? Should they have made public mention and condemnation of these occurrences? Does their silence cast doubt on their honesty as historians? To this question Kaye's book provides no clear basis for an answer.

It is intriguing to ask about Harvey Kaye's own ideological orientation. He makes it clear in the Preface that his book is a sympathetic treatment of the circle of British Marxist historians, and in fact he acknowledges feedback and comments from several of these authors. His later book, The Education of Desire: Marxists and the Writing of History, is likewise committed to defending the insights offered by Western Marxist historians. So his is something of an insider's account of the Historians' Group. We can ask, then, whether Kaye's own sympathies have colored his assessment of the objectivity and rigor of the historians in this group. Does he bring the necessary critical edge that we would expect from an historiographic assessment of a group of historians? (I should confess too that the historians that Kaye studies are also among my list of favorites as well. I would add Marc Bloch and a few others from French and German history, but the broad framework of historical narrative and analysis developed by Dobb, Hilton, Thompson, and Hobsbawm is one that has been powerful for me as well.)

My own assessment is that Kaye's sympathies do not distort his interpretations of these historians. Rather, he offers a careful, reflective, and knowledgeable analysis of the development of their historical ideas and the relations that emerged among them, and he documents the willingness of these historians to avoid the dogmas of CP-driven "party lines" about history. For example, Kaye's critique of Hobsbawm's continuing use of the base-superstructure model illustrates Kaye's willingness to apply a critical eye to these historians (154 ff.). Only obliquely does he address the hardest question, however: did these historians speak out about the atrocities and crimes of Stalinism? Many of these figures (not including Hobsbawm or Dobb) rejected Stalinism through their decision to leave the British Communist Party after the Soviet brutal use of force against Hungary in 1956. But this is still less than forthright recognition of the horrendous crimes of the Soviet dictatorship throughout the 1930s and 1940s, extending through the death of Stalin and beyond.

The penultimate paragraph of the book appears to encapsulate Kaye's own perspective as well as the collective view he attributes to the group of Marxist historians he considers:

In other words, they [British Marxist historians] have accepted that the making of a truly democratic socialism -- or libertarian communism, requires more than 'necessity' -- the determined struggle against exploitation and oppression -- and more than organization. It also requires the desire to create an alternative social order. And yet, even that is not enough. There must be a 'prior education of desire' for, as William Morris has warned: 'If the present state of society merely breaks up without a conscious effort at transformation, the end, the fall of Europe, may be long in coming, but when it does, it will be far more terrible, far more confused and full of suffering than the period of the fall of Rome.'

And this passage perhaps expresses an appealing resolution as well to the question of how to reconcile political commitment with historical objectivity.

(Ronald Grigor Suny has written quite a bit of interesting material on the falsifications offered by "Stalinist history". A few snapshots of his views can be found here: "Stalin, Falsifier in Chief: E. H. Carr and the Perils of Historical Research Introduction" and "The Left Side of History: The Embattled Pasts of Communism in the Twentieth Century".)

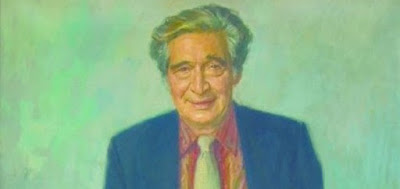

Eric Hobsbawm's history of the Historians' Group

The British historian Eric Hobsbawm was a leading member of the British Communist Party-affiliated Historians' Group. This was a group of leading British historians who were members of the British Communist Party in the 1940s. In 1978 Hobsbawm wrote a historical memoir of the group recalling the important post-war decade of 1946-1956, and Verso Press has now republished the essay online (link). The essay is worth reading attentively, since some of the most insightful British historians of the generation were represented in this group.

The primary interest of Hobsbawm's memoir, for me anyway, is the deep paradox it seems to reveal. The Communist Party was not well known for its toleration of independent thinking and criticism. Political officials in the USSR, in Comintern, and in the European national Communist parties were committed to maintaining the party line on ideology and history. The Historians' Group and its members were directly affiliated with the CPGB. And yet some of Britain's most important social historians were members of the Historians' Group. Especially notable were Eric Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill, Edward and Dorothy Thompson, Maurice Dobb, Raphael Samuel, Rodney Hilton, Max Morris, J. B. Jefferys, and Edmund Dell. (A number of these historians broke with the CPGB after 1956.) Almost all of these individuals are serious and respected historians in the first rank of twentieth-century social history, including especially Hobsbawm, Hill, E.P. Thompson, Dobb, and Hilton. So the question arises: to what extent did the dogmatism and party discipline associated with the Communist Party since its origins influence or constrain the historical research of these historians? How could the conduct of independent, truthful history survive in the context of a "party line" maintained with rigorous discipline by party hacks? How, if at all, did British Marxist historians escape the fate of Lysenko?

The paradox is clearly visible in Hobsbawm's memoir. Hobsbawm is insistent that the CP members of the Historians' Group were loyal and committed communists: "We were as loyal, active and committed a group of Communists as any, if only because we felt that Marxism implied membership of the Party." And yet he is equally insistent that he and his colleagues maintained their independence and commitment to truthful historical inquiry when it came to their professional work:

Second, there was no 'party line' on most of British history, and what there was in the USSR was largely unknown to us, except for the complex discussions on 'merchant capital' which accompanied the criticism of M. N. Pokrovsky there. Thus we were hardly aware that the 'Asiatic Mode of Production' had been actively discouraged in the USSR since the early 1930s, though we noted its absence from Stalin's Short History. Such accepted interpretations as existed came mainly from ourselves— Hill's 1940 essay, Dobb's Studies, etc.—and were therefore much more open to free debate than if they had carried the by-line of Stalin or Zhdanov....

This is not to imply that these historians pursued their research in a fundamentally disinterested or politically neutral way. Rather, they shared a broad commitment to a progressive and labor-oriented perspective on British history. And these were the commitments of a (lower-case) marxist interpretation of social history that was not subordinate to the ideological dictates of the CP:

Third, the major task we and the Party set ourselves was to criticise non-Marxist history and its reactionary implications, where possible contrasting it with older, politically more radical interpretations. This widened rather than narrowed our horizons. Both we and the Party saw ourselves not as a sect of true believers, holding up the light amid the surrounding darkness, but ideally as leaders of a broad progressive movement such as we had experienced in the 1930s.... Therefore, communist historians—in this instance deliberately not acting as a Party group—consistently attempted to build bridges between Marxists and non-Marxists with whom they shared some common interests and sympathies.

So Hobsbawm believed that it was indeed possible to be both Communist as well as independent-minded and original. He writes of Dobb's research: "Dobb's Studies which gave us our framework, were novel precisely because they did not just restate or reconstruct the views of 'the Marxist classics', but because they embodied the findings of post-Marx economic history in a Marxist analysis." And: "A third advantage of our Marxism—we owe it largely to Hill and to the very marked interest of several of our members, not least A. L. Morton himself, in literature—was never to reduce history to a simple economic or 'class interest' determinism, or to devalue politics and ideology." These points are offered to support the idea that the historical research of the historians of this group was not dogmatic or Party-dictated. And Hobsbawm suggests that this underlying independence of mind led to a willingness to sharply criticize the Party and its leaders after the debacle of 1956 in Hungary.

But pointed questions are called for. How did historians in this group react to credible reports of a deliberate Stalinist campaign of starvation during collectivization in Ukraine in 1932-33, the Holodomor? Malcolm Muggeridge, a left journalist with a wide reputation, had reported on this atrocity in the Guardian in 1933 (link). And what about Stalin's Terror in 1936-1938, resulting in mass executions, torture, and the Gulag for "traitors and enemies of the state"? How did these British historians react to these reports? And what about the 1937 show trials and executions of Bukharin, Zinoviev, Kamenev, and Rykov, along with hundreds of thousands of other innocent persons? These facts too were available to interested readers outside the USSR; the Moscow trials are the subject of Arthur Koestler's Darkness at Noon, published in 1941. Did the historians of the Historians' Group simply close their eyes to these travesties? And where does historical integrity go when one closes his eyes?

Arthur Koestler, George Orwell, and many ex-communist intellectuals have expressed the impossible contradictions contained in the idea of "a committed Communist pursuing an independent and truth-committed inquiry" (link, link, link). One commitment or the other must yield. And eventually E. P. Thompson came to recognize the same point; in 1956 he wrote a denunciation of the leadership of the British Communist Party (link), and he left the Communist Party in the same year following the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian uprising.

Hobsbawm's own career shows that Hobsbawm himself did not confront honestly the horrific realities of Stalinist Communism, or the dictatorships of the satellite countries. David Herman raises the question of Hobsbawm's reactions to events like those mentioned here in his review of Richard Evans, Eric Hobsbawm: A Life in History and Eric Hobsbawm, Interesting Times: A Twentieth-Century Life (link). The picture Herman paints is appalling. Here is a summary assessment directly relevant to my interest here:

However, the notable areas of silence -- about Jewishness and the crimes of Communism especially -- are, ultimately, devastating. Can you trust a history of modern Europe which is seriously misleading about the French and Russian Revolutions, which barely touches on the Gulag, the Holocaust and the Cultural Revolution, which has so little to say about women and peasants, religion and nationalism, America and Africa?

And what, finally, can we say about Hobsbawm's view of Soviet Communism? In a review called "The piety and provincialism of Eric Hobsbawm", the political philosopher, John Gray, wrote that Hobsbawm's writings on the 20th century are "highly evasive. A vast silence surrounds the realities of communism." Tony Judt wrote that, "Hobsbawm is the most naturally gifted historian of our time; but rested and untroubled, he has somehow slept through the terror and shame of the age." Thanks to Richard Evans's labours it is hard to dispute these judgments. (199-200)

Surely these silences are the mark of an apologist for the crimes of Stalinism -- including, as Herman mentions, the crimes of deadly anti-semitism in the workers' paradise. Contrary to Hobsbawm, there was indeed a party line on the most fundamental issues: the Party's behavior was to be defended at all costs and at all times. The Terror, the Gulag, the Doctors' Plot -- all were to be ignored.

Koestler's protagonist Rubashov in Darkness at Noon reflects on the reasons why the old Bolsheviks would have made the absurd confessions they offered during the Moscow show trials of the 1930s:

The best of them kept silent in order to do a last service to the Party, by letting themselves be sacrificed as scapegoats -- and, besides, even the best had each an Arlova on his conscience. They were too deeply entangled in their own past, caught in the web they had spun themselves, according to the laws of their own twisted ethics and twisted logic; they were all guilty, although not of those deeds of which they accused themselves. There was no way back for them. Their exit from the stage happened strictly according to the rules of their strange game. The public expected no swan-songs of them. They had to act according to the text-book, and their part was the howling of wolves in the night....

This is the subordination of self to party that was demanded by the Communist Party; and it is still hard to see how a committed member of the Communist Party in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s could escape the logic of his or her commitment. Personal integrity as an intellectual was not part of the bargain. So the puzzle remains: how could a Hobsbawm or Thompson profess both intellectual independence and commitment to the truth in the histories they write, while also accepting a commitment to do whatever is judged necessary by Party officials to further the cause of the Revolution?

Regrettably, there is a clear history in the twentieth century of intellectuals choosing political ideology over intellectual honesty. Recall Sartre's explanation of his silence about the Gulag and the Soviet Communist Party, quoted in Anne Applebaum's Gulag:

“As we were not members of the Party,” he once wrote, “it was not our duty to write about Soviet labor camps; we were free to remain aloof from the quarrels over the nature of the system, provided no events of sociological significance occurred.” On another occasion, he told Albert Camus that “Like you, I find these camps intolerable, but I find equally intolerable the use made of them every day in the bourgeois press.” (18)

So much better is the independence of mind demonstrated by an Orwell, a Koestler, a Camus, or a Muggeridge in their willingness to recognize clearly the atrocious realities of Stalinism.

(Here is an earlier post on the journal created by the Historians' Group, Past & Present; link. And here are several earlier posts about post-war Marxist historians; link, link, link.)

We actually read Capital!

“So, what did you do over the summer”? Most students respond to this ubiquitous question with the familiar answers: “caught up with family”, “earned some money” or (perhaps more commonly) “lots of daytime drinking”. For a small group of political economy students from the University of Sydney, however, they might respond: “I read Marx’s Capital, volume 1”.

Between November, 2015 and March, 2016 a small, dedicated group of students – undergraduate, postgraduate, or between degrees – met weekly to discuss that text which too-few Marxists have actually read: Capital. Meeting largely at the University of Sydney, the group persevered through the entire 682 pages, despite the oppressive heat of a Sydney summer (intensified by the contradiction of capitalism that is climate change).

Running through the weekly discussions were themes including the specificity of capitalism, the continued relevance of this historical text, and questions of Marxist strategy moving forward into the 21st century. Below are some of the thoughts and impressions of just some of these students.

Matthew Ryan – Postgraduate student

It’s quite a broad brief, “say something about your experience reading Capital”. Do I focus on a particular concept, something I never understood but now grasp a little better? Do I talk about the relevance of the text in the twenty-first century? Perhaps I can comment on an ongoing debate within Marxism, and offer my personal resolution through reference to the text? All valid options and it would be easy to write too many words on any of these topics. But instead, I’m going to talk about reading Capital.

David Harvey has taught a class on Capital every year for decades. Well, maybe he’s missed a few on leave and what not, but the point is he has read it many times! I always used to wonder why he read it again each year. Having now read it myself, I can understand why – different groups and different approaches to reading the text all result in a unique, contingent experience of the text. This can be seen even through our own short encounter with the text.

Some people would watch Harvey’s lectures on Capital before each week’s meeting, as well as the chapter. Some would watch the video then read the chapter, while others would do the opposite. Some read companions to Capital in parallel, whilst others supplemented their reading with online resources – glossaries of concepts, and the like. Some people read earnestly, taking notes, and bringing these as discussion points. Others had a more organic reading process, and a discussion style to match. The point is there are a lot of ways to read it. And if I’m honest, my own approach was a mix of almost all of these, resulting in different experiences with different chapters.

A further variable producing different, yet equally stimulating, readings were the backgrounds and interests of those in the group. Some came to the group with a wealth of knowledge of Marx and Marxism, while others (myself included) did not know their absolute from their relative surplus-values. Personal research interests varied from the role of technology in capitalism, to issues relating to profit rate, to colonisation and class formation, through to the historical specificity of capitalism and the agency of class actors in capitalist development. Each brought a different perspective, leading the conversation in suggestive and distinct directions. I’m sure no reading group would have the same experience.

Reading Capital was a wholly social experience – or, I should say, a socially contingent experience – and I’m sure I’ll be telling friends, family, and students about my reading of Capital in the summer of 2015-16 for many years to come.

Rhys Cohen – Tutor and Honours graduate

For me there were two really significant things that I got from the reading group – the first was to do with the content of the book and its modern context, and the second was to do with the social experience and practice of the exercise.

First, something that Llewelyn in particular was keen to draw our attention to, was the extent to which our engagement with more contemporary Marxian literature tended to cloud our reading of Capital. I know personally that many times I assumed Marx was making an argument that was much more sensitive, nuanced and, for want of a better word, acceptable for modern theorists than was actually the case.

It took conscious effort to read the book on its own terms and it was confronting to see some of the limitations that Marx is so often criticised for. But in many ways this was heartening because it reaffirmed to me the huge contributions that theorists since Marx have made to the understanding and critique of capitalism, and also the necessity for this project to continue.

Second, as young, Left students I think we had all become very familiar with the standard lamentations of the Left more broadly: how can we stop this constant infighting, factionalism etc. The absurdity of these divisions was something we had all discussed at length in the past. And going into the reading group, although we all respected each other as friends and colleagues, I felt some anxiety as to whether this would remain the case, or if we might find some fundamental rift emerging between us.

And some conflicts did emerge: we argued about determinism, structuralism and agency; the nature of class and intersectionality; technology, morality and communism. At times these arguments got quite heated. But what struck me was our capacity to stick with the project, to work through the arguments. And in the end I felt that not only were many of these divisions revealed to be largely semantic miscommunications, but that we had moved closer to each other’s understandings in a way that felt constructive as opposed to coercive.

Llewellyn Williams-Brooks – Honours student

Returning to the New Left critique of Australian History

It certainly is a strange to read Capital in the context of Australia: a country straddling the contradictions of core and peripheral development within global capitalism. This precariousness, in terms of the world market, has always made Australia something of a strange case in the scheme of things. After all, Australia in the 19th century was producing a third of the British gold-standard’s reserve while it was championing the 8-hour work day and birthing a major union movement and Labor party. There seems something of an uncertainty, perhaps, a contradiction, at the very heart of Australianess. This economic uncertainty was best expressed, in the language of political office, through Paul Keating’s ‘Banana Republic’. Conversely, the nationalist writers were quick to convert this ambiguity into a mythical treatment of egalitarianism, most famously addressed in Ward’s Australian Legend, and necessarily critiqued by McQueen in A New Britannia and Irving and Connell’s Class Structure in Australian History. This was the project of the old and the new left, but this is not our project.

Wakefield is seen to observe, in the final section of Capital, that social relations of production are not reducible to simply a cloned relocation of the economic and political apparatus in Britain.

As Marx comments: “[Wakefield] discovered that capital is not a thing, but a social relation between persons, established by the instrumentality of things”. Australian colonialism required the re-establishment of the old relationships within a complex set of new social relations.

This reading substantiates that by understanding the economic relations of capitalism, we have, in the most optimistic reading, only half the picture. We should also observe the necessity of positioning the agency of resistance in the centre of human social history. We must neither fall into the trap of accepting Australia as a ‘peripheral’ banana republic, or a mythical space of elite nationalism. Instead we should understand that resistance in Australia is a fact of our history: Indigenous resistance in the frontier-wars, the militant organising of the great strikes, and the women’s suffrage movement are all evidence of this fact. Marx’s Capital only gets us part of the way, we must take hold of our own social history in order to change it.

Joel Griggs – Honours student

Reading Capital in its entirety is like reading Marx for the first time. For a self-professed Marxist, the experience is both one of vindication and sobriety. On the one hand I feel the hubris that Marx inspired in me from the very outset. On the other, a deep trepidation begging an answer to the question: What if Marx was right?

Incidentally, as an undergraduate embarking upon my honours year, I am repeatedly reminded that Marxism is experiencing a kind of academic renaissance. What is driving this resurgence is anyone’s guess but as my comrades and I wade through the murky waters from commodity fetishism to Marx’s own theory of colonisation I am struck by the powerful clarity of a man whose perspicacity eclipses the moral dilemma evident on every page. Less than two years after a young American Union formally abolished slavery, Marx is alone in revealing a new kind of slavery emerging in the Old World. Waged-labour with its ‘freedom in the double sense’ replaced the stability of the indentured peasant with the precariousness of the proletariat; a class at once pitted against one another and unified in their wretched struggle.

It is this constant dialectical relationship present throughout Capital that exposes the structure and the structural weaknesses of our predicament. While the conditions have undeniably improved, the structural realities of the working class remain largely unchanged today. Likewise, even though the capitalism that so consumed Marx in the nineteenth-century may have traded in its ostentatious top hat for a less-assuming tie, it is nonetheless the same vampiric fiend that dogs every step of our collective existence.

Capital’s strength lies in its piercing internal critique of what defines capitalism. Twenty-first century capitalism is adaptable, mobile, and has a thousand faces. To assign capitalism homogeneity is to lose before we have even begun to unravel its web. The uneven development of capitalism, too, makes it equally difficult to analyse. There must be, however, an underlying logic that serves as a motor for capitalism. To this end, Marx’s unfinished project is no less mistaken today than it was one and a half centuries ago – though like most things in life, questions of right and wrong are seldom black and white. The answer for me lies within the explanatory scope of the theory. For an exploration into the insights of an exceptional dialectician, then, my hubris and trepidation seem entirely fitting. More relevant today than ever, reading Capital has been a wonderful and enlightening experience.