War

Comparison Is the Way We Know the World

I’m not arguing that because other people have made the same comparison I have, I am right. What I am trying to do is add a time dimension to this conversation. What struck me about this comparison is that King made it three years before Israel imposed the siege regime on Gaza. And it was the time dimension that was also absent from the challenges that the reporter offered yesterday, when she talked about population density and the smuggling of weapons. The population of the ghettos changed over time (and weapons were indeed smuggled in).

How Am I?

I am an Arab woman who studies the Middle East. My students know what I believe and what I am grieving every day. It is on my face, in my posture. Even as my field of study comes under attack, as those who research the Middle East are criminalized and subject to harassment, my friends and I continue doing what little we can to live with ourselves. We organize teach-ins and edit statements and donate money and go to protests and vigils and scream for people’s right to live while our university endowment helps fund the missiles killing Palestinian children.

Making Endless War: The Vietnam and Arab-Israeli Conflicts in the History of International Law – review

In Making Endless War: The Vietnam and Arab-Israeli Conflicts in the History of International Law, Brian Cuddy and Victor Kattan bring together essays exploring attempts to develop legal rationales for the continued waging of war since 1945, despite the general ban on war decreed through the United Nations Charter. Linked through a nuanced comparative framework, the essays in this timely collection show how these different conflicts have shaped the international laws of war over the past eight decades, writes Eric Loefflad.

Making Endless War: The Vietnam and Arab-Israeli Conflicts in the History of International Law. Brian Cuddy and Victor Kattan. University of Michigan Press. 2023.

For Jeff Halper, an American-Israeli anthropologist, co-founder of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, and proponent of a single democratic state in historic Palestine, the decision to become an Israeli in the first place had a great deal to do with the Vietnam War. True to the counter-culture protests that arose in response to the War, the activist Halper, like so many young, idealistic American Jews of his era, viewed Israel as a more direct conduit to his heritage than a homogenising suburban upbringing could ever allow for. This search for meaning was coupled with a widespread difference in how the Vietnam War and Israel’s wars were broadly characterised in Halper’s contexts of influence. For many Americans who opposed intervention in Southeast Asia, Israeli violence differed in its “purity of arms.” According to this framing, in direct contrast to an American government waging wars half a world away, Israel zealously fought for its very survival right at its doorstep. It was witnessing the demolition of Palestinian homes to make way for Israeli settlers in the West Bank that caused Halper to renounce this narrative and rededicate his life.

For Jeff Halper, an American-Israeli anthropologist, co-founder of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, and proponent of a single democratic state in historic Palestine, the decision to become an Israeli in the first place had a great deal to do with the Vietnam War. True to the counter-culture protests that arose in response to the War, the activist Halper, like so many young, idealistic American Jews of his era, viewed Israel as a more direct conduit to his heritage than a homogenising suburban upbringing could ever allow for. This search for meaning was coupled with a widespread difference in how the Vietnam War and Israel’s wars were broadly characterised in Halper’s contexts of influence. For many Americans who opposed intervention in Southeast Asia, Israeli violence differed in its “purity of arms.” According to this framing, in direct contrast to an American government waging wars half a world away, Israel zealously fought for its very survival right at its doorstep. It was witnessing the demolition of Palestinian homes to make way for Israeli settlers in the West Bank that caused Halper to renounce this narrative and rededicate his life.

the collection centres on the broad theme of how mostly American and Israeli lawyers, statesmen and military officers used issues that arose in the two conflicts to proclaim exceptions to the general ban on war as entrenched in 1945 through the United Nations Charter.

While Halper’s journey may be a unique one, it is nevertheless a testament to how intersections between post-Second World War conflict in Southeast Asia and the Middle East shaped the lives of so many different people in so many different ways. For anyone interested in how this multitude of individual experiences might be understood in relation to broader systemic forces, especially the variable medium for navigating “legitimate” violence deemed the “laws of war”, historian Brian Cuddy and international lawyer Victor Kattan’s Making Endless War is an invaluable resource. Comprised of ten robust chapters and an insightful forward by Richard Falk (a leading international legal critic of the Vietnam War and later the one-time United Nations Special Rapporteur for the Occupied Palestinian Territories), Making Endless War proceeds on a roughly chronological basis from 1945 to the present day, tracing developments and unearthing connections between the two (meta-)conflicts. With chapters confronting a variety of issues from multiple perspectives, the collection centres on the broad theme of how mostly American and Israeli lawyers, statesmen and military officers used issues that arose in the two conflicts to proclaim exceptions to the general ban on war as entrenched in 1945 through the United Nations Charter. While its detailing of legal doctrine is truly world-class, Making Endless War’s revelation of the individual personalities, diplomatic intrigue and political struggles behind ostensibly “apolitical” technicalities is equally outstanding.

Vietnam, emboldened by its resistance to the US, led efforts in the 1970s to include non-state national liberation movements within a regime of the laws of war that hitherto only granted rights to state actors.

One illustration of how this text accomplishes its multi-faceted, but nevertheless cohesive, focus across chapters concerns the debate on the revision of the laws of war via two Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions. In Chapter Five, Amanda Alexander explores the significance of how Vietnam, emboldened by its resistance to the US, led efforts in the 1970s to include non-state national liberation movements within a regime of the laws of war that hitherto only granted rights to state actors. Following this, in Chapter Six, Ihab Shalbak and Jessica Whyte centre the Janus-faced quality of what this revision meant for the Palestinians. While it provided their cause with a newfound degree of institutional legitimation, it also constrained Palestinian efforts to unite themselves as a revolutionary people whose struggle could not be divided along the lines presumed by the law. From here, co-editor Victor Kattan presents an account in Chapter Seven of how Israel moved from being the sole dissident resisting revision in the 70s (due to its application to the Palestinians) to being joined by the US in the 80s. This coincided with the ascent of the Reagan Administration in the 80s where an influential grouping of Neoconservatives and Vietnam veterans – invoking arguments pioneered by Israel – similarly prevented the US from ratifying the Geneva Convention’s Additional Protocols. Finally, in Chapter Eight, Craig Jones examines how, despite their nations’ disavowal, American and Israeli lawyers became adept at using the laws of war to enable, as opposed to constrain, violence through developing a regime of so-called “operational law” that integrated international and domestic legal standards in a manner “…designed specifically to furnish military commanders with the tools they required for ‘mission success’” (215).

With the ascent of the Reagan Administration in the 80s […] an influential grouping of Neoconservatives and Vietnam veterans – invoking arguments pioneered by Israel – similarly prevented the US from ratifying the Geneva Convention’s Additional Protocols

When reading Making Endless War in this present moment, it is naturally impossible to disconnect its insights from the most recent bloodshed in Israel-Palestine that erupted almost immediately following the collection’s release. Fortuitous in the most horrific way possible, Cuddy and Kattan provide an invaluable service in exposing the impossibly high stakes of the despair invoking “endlessness” that animates their collection’s poignant title. However, by connecting the greater Arab-Israeli conflict to the Vietnam War, the editors make a significant contribution in decentring the widespread viewpoint that the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is fundamentally unique – a presumption that unites pro-Israel and pro-Palestine advocates who agree on virtually nothing else. In this way, Making Endless War provides a powerful statement on how episodes of violence, however specific they might appear, cannot be understood independent of greater forces – including (and perhaps especially) the principles and institutions that present their mission as an effort to constrain armed conflict. As such, Cuddy and Kattan’s collection can be viewed as a major innovation in building a greater genealogy of global violence.

Making Endless War provides a powerful statement on how episodes of violence, however specific they might appear, cannot be understood independent of greater forces – including (and perhaps especially) the principles and institutions that present their mission as an effort to constrain armed conflict.

While their comparative framework might be viewed as limited in its representations, the editors are eminently aware of this, and this very awareness forms a cornerstone of their methodology. On this point, they deliberately confront the significance of how, especially within the centres of global power, “[t]he Vietnam War and the multiple Arab-Israeli conflicts became cultural moments that captured the public imagination in ways few other conflicts did, even those that were more lethal (262).” With this comparative captivation itself an important finding, there is no reason why the insights developed through Making Endless War cannot be extended to include the multitude of other forces, fixations, and personalities that can be located within the many ideologies of war that shape our lives. The Palestinian-Israeli conflict is a particularly vast and gut-wrenching repository of said ideologies. Sadly, there is no shortage of material for interested scholars to draw upon.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Michiel Vaartjes on Shutterstock.

Philosophy’s Importance in “Times Like These”

The Los Angeles Review of Books has just concluded publishing a series of articles on the importance of philosophy in “times like these”.

What are “times like these”? The editor of the series, George Yancy (Emory), describes them as “trying times… moments of existential ruin, where we are 90 seconds to midnight, which is the closest we have ever been to global catastrophe.”

The contributors to the series are Elizabeth Brake (Rice), Lori Gallegos (Texas State), Jay Garfield (Smith), Kate Manne (Cornell), Todd May (Warren Wilson), and Vanessa Wills (George Washington). You can find the links to each of their pieces in the last two paragraphs of Professor Yancy’s introductory essay.

One thing I noticed about the series was its emphasis on right now. That was probably its brief, but I think it could also be worthwhile to adjust our focus, to better look at things from a distance.

Such distance might lead us to question the generalization of “times like these.” There are indeed horrible things happening, and Yancy’s references to Gaza, racism, and climate change are just a few of many well known examples. Some of these terrible things we may come to through personal experience, some mainly via ever-present news and social media, so it’s no surprise that they dominate our consciousness. Yet at any given time, countless things, good and bad, are happening. And if we take the long view (50 years? 100 years? 500 years?) we can see that in certain respects and for certain populations, “times like these” are preferable in comparison (e.g., standards of living, racism, sexism, medicine, access to information, etc.). Of course, “preferable in comparison” doesn’t mean “problem free.” It doesn’t even mean “not terrible.” But it complicates the picture somewhat.

One of the ways we’re better off—and this is building on what Elizabeth Brake says in her essay—is that we have concepts, ideas, and norms in sufficient circulation for us to better identify and understand our problems. So, in one way, things seeming worse may be a function of us having better conceptual tools by which to diagnose our situation.

Here’s what Brake says:

Too often, when pressed to defend the discipline, professional philosophers focus on philosophy’s use as a tool for rigorous argumentation and clear conceptual analysis. The idea here is that philosophy teaches the skills we need for reasoned disagreement with our fellow citizens, to avoid talking past one another and to take others’ perspectives seriously. But I find that this downplays the fact that philosophy does, and has always done, more than teach us how to argue: it generates new concepts, new tools and devices for understanding the world—and for reshaping it.

Of course, the skills of argument and critical thinking that philosophy teaches are invaluable. But these skills are valuable only so long as our fellow citizens are willing to engage in a reasonable discussion of our differences and won’t simply seek to impose their will by force. My fear is that there are times, and this might be one of them, when this condition does not obtain.

On the other hand, in the face of such things, the philosophical temptation may be quietism—the belief that the only thing to do, given our sense of powerlessness, is go inward toward the personal contemplation of Truth and Beauty, or to tend to one’s own garden. Indeed, there has lately been a resurgence in interest in the philosophy of stoicism in self-help circles.

In my view, though, both of these philosophical responses underestimate what philosophy offers: a chance to communicate with others who are interested in what we have to say and, through that communication, to initiate change. Philosophy is a powerful tool for creating and recrafting concepts that reflect our experiences and what we take to be normatively important about them; it is also a powerful tool for interrogating the ideals that guide us and asking whether we, personally and socially, really live up to those ideals. In this, philosophy offers us no less than a chance to remake the world—a possibility for creative conceptual engineering that can articulate what we previously could not and suggest alternate practices that better reflect our ideals.

Yet philosophy takes time. Not just for its production and for the filtering of worthwhile ideas, but also for ideas to get carried from academia into broader society. And it takes more time still for them to come to be a part of the predominant attitudes and beliefs in a society, the ideas people think with, such that they can play a role in efforts to “remake the world”.

So in considering the value of philosophy in “times like these,” a portion of our attention should be not on what philosophers should do now, but on what philosophers have already done that provide us with the epistemic, conceptual, and normative tools by which we make sense of these times and what we should do in them. Such an accounting may take us decades, centuries, or even millennia into the past, and show us that more of philosophy is more valuable today than many might think.

The post Philosophy’s Importance in “Times Like These” first appeared on Daily Nous.

Cartoon: A taste of his own war crimes

Help keep this work sustainable by joining the Sorensen Subscription Service! Also on Patreon.

Support the Troops: Military Obligation, Gender, and the Making of Political Community – review

In Support the Troops: Military Obligation, Gender, and the Making of Political Community, Katherine Millar analyses “support the troops” discourses in the US and UK during the early years of the global war on terror (2001-2010). Millar’s is a nuanced and powerful study of shifting civilian-military relations – and more broadly, of political community and belonging – in liberal democracies, writes Amy Gaeta.

Read an interview with Katherine Millar about the book published on LSE Review of Books in March 2023.

Support the Troops: Military Obligation, Gender, and the Making of Political Community. Katherine Millar. Oxford University Press. 2022.

Katherine Millar’s Support the Troops identifies the emergence of calls to “support the troops” in the US and UK and asks what this discourse not only represents about political community and gender relations, but how this call mobilises public support for wars they may also oppose.

Katherine Millar’s Support the Troops identifies the emergence of calls to “support the troops” in the US and UK and asks what this discourse not only represents about political community and gender relations, but how this call mobilises public support for wars they may also oppose.

Millar contextualises “support the troops” within the normative construction of civilian-military relations in liberal democracies, and in doing so, challenges what she calls “the good story of liberalism” by tracing how liberalism has feigned moral superiority and structure by distancing itself from the military violence upon which it relies for maintenance (xx).

Millar contextualises ‘support the troops’ within the normative construction of civilian-military relations in liberal democracies, and in doing so, challenges what she calls ‘the good story of liberalism’

Across eight chapters, Millar assembles an impressive and varied archive of calls to support the troops, including speeches, media reports, government press releases, bumper stickers, adverts, and more. The book is guided by the feminist methodological impulse to confront uncertainty and partiality in our objects of study. In other words, it is refreshing that Millar admits this impressively researched book is guided by a series of unanswered questions that emerged in her personal experience of living in Canada during the Iraq War. These questions include, “can you oppose a war while still living in community” (x) and “why do we think we have to [support the troops]?” (xi). Also impressive is Millar’s choice to not focus on individuals’ reasons for why they do or do not support the troops. By focusing on the larger patterns in discourse, Support the Troops offers a more applicable and comparative work that enables readers to appreciate the slight, yet telling difference in US and UK civil-military relations and their formation.

Millar refuses easy equations and assumptions, namely the notion that “support the troops” is yet another site of militarism.

In this exploration, Millar refuses easy equations and assumptions, namely the notion that “support the troops” is yet another site of militarism. Rather than providing an answer, Millar instead demonstrates that militarism is simply not a productive analytical framing. Using the analytic of “discursive martiality,” she treats the military as a “discourse of gendered obligation and socially generative violence” and aims to follow how it moves and what it forecloses (35).

The idea that serving and thereby being willing to go to war and possibly die or become disabled for one’s country, is a key quality of what it meant to be a ‘good citizen,’ a deeply masculinised and racialised ideal.

Central to her investigation of support the troops discourse is the liberal military contract, a binding element of modern-day liberal democracies. Namely, the contract is the idea that serving and thereby being willing to go to war and possibly die or become disabled for one’s country, is a key quality of what it meant to be a “good citizen,” a deeply masculinised and racialised ideal. In earlier 20th-century wars, namely the World Wars, attacks on the domestic front, such as the aerial bombing of civilian areas in the UK, cultivated a shared sense of vulnerability among publics with the military and therefore obligation to sacrifice something in service of the war, Millar argues. As such, by World War Two, the expectation that everyone should do one’s part for the war – no matter the war – became domesticated, “experientially, affectively, and ideologically within the US and UK” (52). Structurally then, this further sedimented the feminisation of the domestic front – providing charity and care labour and making sacrifices at home – and the masculinisation of the war front – being willing to die to protect their nation and the feminised home front.

Particularly illuminating about Millar’s project is her tracing of how different wars produced different discursive formations of military personnel and therefore civilian-military relations. A memorable example is the refrain of “our boys” during the Vietnam War which framed soldiers as innocent, emphasising their youth and pre-empting how the experience of war would rush them into “manhood” (55). The innocent angle also firmly contrasts the horrors of the Vietnam War enacted by US soldiers.

The pluralised and more passive formation of the “troops” still requires the support of the public, posing important questions about what the troops need support for, and what support the military and government are failing to provide them that the public must supplement.

Once again, today, civilian-military relations are in flux for civilians living in liberal democracies. War is something that happens “over there,” and no longer do eager citizens enlist in hoards and go to war overseas, nor are they drafted, although military recruitment campaigns are still going strong. In tandem, many military service jobs appear as rather mundane, and this may impact the social importance and status of soldiers and soldiering to classed, racialised, and gendered ideas of civilised and ultimately “good” citizenship. Millar argues that these changes contribute to a shift in the gendered structure of the liberal military contract’s relationship to normalising violence. Whereas in past wars, where killing and dying for the state were key to masculinised normative citizenship, now “violence is presented as incidental to war, something that ‘happens’ to the vulnerable, structurally feminized troops” (102). The pluralised and more passive formation of the “troops” still requires the support of the public, posing important questions about what the troops need support for, and what support the military and government are failing to provide them that the public must supplement.

Millar’s text is extremely pertinent in a political era of cyberwar, drone warfare, and other forms of warfare that do not require the same degree of physical and geographical mobilising of troops.

Millar’s text is extremely pertinent in a political era of cyberwar, drone warfare, and other forms of warfare that do not require the same degree of physical and geographical mobilising of troops. As an academic working across questions of disability, gender, and contemporary US militarisation, I found Millar’s project to offer generative questions about how political community emerges differently when the ready-to-die cisgender-heterosexual-male idea of a solider and the violence inflicted by war is moved out of the view of the domestic front, especially when that figure is not even physically present in geographically defined spaces of conflict and war.

The book did leave me wanting a more robust analysis of the relationship between “good citizenship,” Whiteness, and masculinity, all of which are deeply shaped by the violence that underpins the “good” story of liberalism and civilian-military relations – although Millar certainly does not ignore or deny those connections. Yet, this may also be read as an opportunity for scholars to examine how changes in military service expectations and roles affect the ways that racial structures shift in accordance.

Millar’s investigation of the discursive patterns around “support the troops” begs questions about what happens when a minority or a wider segment of the public refuses to give such support.

Support the Troops is a powerful text that invites readers to think carefully about the present-day formation of political community and belonging in liberal democracies. Millar’s investigation of the discursive patterns around “support the troops” begs questions about what happens when a minority or a wider segment of the public refuses to give such support. As large waves of state-critical activism and civil protests continue to sweep across the US and UK, among other parts of the world, Support the Troops is a crucial touchpoint for understanding the “good story of liberalism” and the types of social contracts it relies upon for cohesion between the state, the military, and citizens.

This post gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: CL Shebley on Shutterstock.

Israel, Hamas, and “Blowback” (guest post)

“The proportionality constraint is backward-looking in the following sense: to determine how bad a prospective harm is for a potential innocent victim, we sometimes need to look at what that victim has suffered in the past, and whether we’re responsible for what they’ve suffered” as well as “whether we should have acted differently in the past thereby avoiding the need to inflict that harm now.”

In the following guest post, Saba Bazargan-Forward (UC San Diego) argues that these backward-looking elements imply that “we should not adopt an ‘ahistorical’ approach when adjudicating proportionality in Israel’s war against Hamas”

It is part of the ongoing series, “Philosophers On the Israel-Hamas Conflict“.

[Paul Apal’kin, “Invasion”]

Israel, Hamas, and “Blowback”

by Saba Bazargan-Forward

Hamas’ attack against Israeli civilians on October 7th, 2023 was not just an act of terrorism but an act of genocide, and should be condemned as such. The brutal attack was shocking in its scope and sadism. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that attacks from Hamas are generally foreseeable consequences of unjust policies Israel has imposed upon Palestinians in Gaza over the past few decades. This supposition, even if true, does not lend moral legitimacy to Hamas’ terrorism. Nor does it mitigate the culpability of Hamas’ leadership. But it does raise this question: if Hamas’ terrorism is “blowback” from unjust Israeli policies toward Gaza, does this affect how Israel is permitted to fight back? Here, I address this question.

War ethics, both in its canonical form and in its more recent revisionary derivations developed since the turn of the century, tends to focus on “the moment of crisis”—the point in time at which a state is seriously considering a resort to war. The problem with assessing the morality of war at the moment of crisis is that sometimes the state considering a resort to war is partly responsible, by having committed past wrongs, for creating the situation in which a resort to war becomes necessary in the first place.

It seems to me that there are at least two special moral considerations restricting how these “blowback” conflicts should be fought, which, in turn affects whether such conflicts can be fought. (I discussed this issue in an article where I focused on the relevance of compensation; here, I consider other factors.)

The first moral consideration relevant to evaluating “blowback” conflicts is this: if Israel has unjustly immiserated Gazan civilians in the recent past, then the collateral harm Israel inflicts in its current war against Hamas harms civilians in Gaza twice over. This is relevant to the comparative weight that these harms should receive when deciding whether to inflict such harms. It is relevant because harming people whom you have already wrongfully harmed is harder to justify than harming people you have not.

To see this, imagine that Rescuer can prevent Innocent from being murdered only by collaterally breaking another innocent person’s arm: person A or person B. They’re identical, except that Rescuer wrongly broke A’s arm last year. If Rescuer chooses the action that collaterally harms A now, she will have thereby infringed A’s rights twice, whereas if she chooses B now, she will have thereby infringed B’s rights once. Since the former is morally worse than the latter, it seems Rescuer should choose B over A. There is a way out: Rescuer could permissibly flip a coin in deciding whom to choose, provided she will compensate A for the independent past harm. But assuming Rescuer won’t compensate A, it seems to me that A has a stronger claim than B against being harmed. A corollary to this claim is that the harm averted to Innocent must be greater to justify breaking A’s arm than B’s arm.

Some might demur. To see why, consider a variant of the case in which the details are the same, except there’s no person B. So, the only way to rescue Innocent is by collaterally harming A. It might seem strange to think that Innocent’s claim to be saved can depend on whether Rescuer unjustly harmed A in the past. After all, Innocent didn’t have anything to do with Rescuer’s past mistreatment of A. Yet it now seems that Innocent must bear the costs of that mistreatment! That seems unfair. It’s true that Innocent’s claim to be saved does not depend on whether Rescuer unjustly harmed A in the past. But it’s also true that Innocent’s claim does indeed depend on the weight of the prospective harm Rescuer will collaterally inflict on A. And I’m suggesting that Rescuer’s past mistreatment of A can affect how we should weigh the prospective harm that Rescuer will collaterally inflict on A in saving Innocent. To be clear, this doesn’t mean that Rescuer shouldn’t save Innocent. Rather, it means that Rescuer’s past mistreatment of A is morally relevant in the decision whether to save Innocent by harming A.

Let me clarify what I’m not claiming. I am not claiming that we always have decisive reasons to prefer harming those we haven’t unjustly harmed in the past over those we have unjustly harmed in the past. There are all sorts of factors that might outweigh or override the relevance of past harms. Rather, I am claiming that past unjust harms can be morally relevant in evaluating prospective harms. I am also not claiming here that past unjust harms for which you’re not responsible are relevant in weighing prospective harms. Though I do certainly think such harms can be relevant, I am not leaning on such a claim here.

This simplistic example in which you must choose between A and B is not meant as an analogy of the situation between Israel and Gaza. Rather, its purpose is more general. It suggests that the proportionality constraint is backward-looking in the following sense: to determine how bad a prospective harm is for a potential innocent victim, we sometimes need to look at what that victim has suffered in the past, and whether we’re responsible for what they’ve suffered. If Israel has indeed unjustly immiserated Gazans over the past few decades, this makes it harder for Israel to satisfy the proportionality constraint now in its current conflict in Gaza.

The second moral consideration relevant to evaluating “blowback” conflicts is this. Assuming Hamas’ terrorism was a foreseeable consequence of unjust Israeli policy toward Gazans, Israel bears some responsibility for the fact that it needs to resort to self-defense now. (Again, I am not claiming that responsibility is zero-sum—Israel’s responsibility for its situation does not diminish Hamas’ responsibility. Nor am I claiming that they are equally responsible, or that they are the only parties responsible). This means Israel bears more responsibility for the deaths of Gazans it collaterally kills than it otherwise would. To see this, imagine you have a neighbor who for no reason at all unjustly attacks you with the intention of breaking your arm. You can defend yourself, but only by engaging in an action that collaterally harms his young child. Now compare this with a nearby case. Imagine you have a neighbor whose car you unjustly vandalize. You suspect, prior to doing so, that in response he will unjustly attack you with the intention of breaking your arm. Again, you can defend yourself, but only by collaterally harming his young child. Holding all the harms fixed in these two cases, it seems that the harm to the child in the second case should be weighed more heavily than the harm to the child in the first case. This is because you can be morally expected to have avoided the harm in the second case but not the first.

Again, this simplistic example is not meant as an analogy of the situation between Israel and Gaza. Rather, it suggests that the proportionality constraint is backward-looking in the following sense: to determine how bad a prospective harm is for a potential innocent victim, we need to look at whether we should have acted differently in the past thereby avoiding the need to inflict that harm now. If this describes Israel’s situation currently, it makes it all the more difficult for Israel to satisfy the proportionality constraint.

The moral is that we should not adopt an “ahistorical” approach when adjudicating proportionality in Israel’s war against Hamas. This is because the proportionality constraint includes important backward-looking elements. If Hamas’ terrorism is “blowback” from unjust Israeli policy toward Gaza, then Gazan lives should be weighed especially heavily. This, in turn, makes it more difficult for Israel to satisfy the proportionality constraint in its conflict against Hamas.

The post Israel, Hamas, and “Blowback” (guest post) first appeared on Daily Nous.

The Goal Is Ethnic Cleansing, Not Defeating Hamas

Notes From The Edge Of The Narrative Matrix

Listen to a reading of this article (reading by Tim Foley):

https://medium.com/media/0f3d660516169063b7a34aea07b555e7/href

❖

The funny thing about Henry Kissinger dying at age 100 is that he lived long enough to become one of the least crazy warmongers in the DC swamp — not because he got saner, but because the US empire has gotten so much crazier. Almost everyone running the US government today is a worse warmonger than Kissinger was at the end of his life.

❖

Sane person: Stop murdering thousands of children.

Crazy person: You hate people because of their religion.

❖

Israeli officials keep openly saying again and again that the plan for Gaza is ethnic cleansing, yet the western political/media class adamantly insists on continuing to frame Israel’s actions in Gaza solely as a war against Hamas. Hamas isn’t the target, it’s the excuse.

Ryan Grim on Twitter: "Netanyahu, according to the Israeli press, has instructed Ron Dermer, his Minister of Strategic Planning and a very close aide, to explore ways to "thin out" the Gaza population. Along with the renewed proposal to push them through the Rafah crossing into Egypt, the English... pic.twitter.com/MTIULDVy0N / Twitter"

Netanyahu, according to the Israeli press, has instructed Ron Dermer, his Minister of Strategic Planning and a very close aide, to explore ways to "thin out" the Gaza population. Along with the renewed proposal to push them through the Rafah crossing into Egypt, the English... pic.twitter.com/MTIULDVy0N

❖

A damning new report from +972 Magazine published on Thursday exposes how Israel has been deliberately striking civilian targets in Gaza as a matter of policy because they believe it will “lead civilians to put pressure on Hamas.” It makes it clear that the IDF is very much aware of where the civilians are, and that when they kill children it’s because they calculated that it would be strategically worthwhile to do so.

❖

As evidence continues to mount that a significant number of the Israelis killed on October 7 were actually killed by indiscriminate fire from the IDF, Israel has announced its plans to bury the vehicles Israelis died in — in other words to bury forensic evidence. According to the Jerusalem Post, “In order to save space and be as environment-friendly as possible… the cars may be shredded before being buried.”

Are people not tired of having their intelligence insulted?

Max Blumenthal on Twitter: "As evidence of friendly fire killings on October 7 mounts, Israel plans to bury cars containing important forensic evidence which were burned in southern Gaza It will shred the cars completely before burying them to "be as environment-friendly as possible" pic.twitter.com/V9prHiqVsn / Twitter"

As evidence of friendly fire killings on October 7 mounts, Israel plans to bury cars containing important forensic evidence which were burned in southern Gaza It will shred the cars completely before burying them to "be as environment-friendly as possible" pic.twitter.com/V9prHiqVsn

❖

Israel’s western allies keep being confronted with the problem that they’ve been framing Israel all these years as a free democracy with liberal values identical to the west’s, yet it keeps acting just like the Evil Dictatorships the west always tries to distinguish itself from.

They keep running into this problem because it’s not something that Israel can actually change about itself, since it’s just the stuff that Israel is made of. The Zionist ideological framework which birthed Israel in the first place is what has been guiding its political course this entire time, and that ideology can only steer the country towards racism, apartheid, fascism, theft, murder and genocide.

This has long caused a dissonance between what Israel is seen doing and what Israel is presented as by its western allies and its own PR, and now that dissonance has soared to unprecedented heights. Westerners are taught (falsely) that their governments embody virtuous values systems prioritizing freedom, peace, justice and truth, and here’s this bizarre ethnostate glommed onto them which very clearly wipes its ass with those values without even really attempting to disguise it.

The western empire has destroyed nation after nation on the premise each of those nations was governed by an Evil Dictator who couldn’t be allowed to remain in power, and yet we’re being asked to look past the actions of an intimate partner of the western empire which make those Evil Dictators look like teddy bears and believe that that partner is actually entirely in alignment with the values of the virtuous west. There’s no way to reconcile these two completely contradictory perspectives, so you get cognitive dissonance.

The more cognitive dissonance there is, the harder it is for people to hold onto these contradictory views simultaneously. Eventually it gets too much to hold on to and they’ve got to let go, which is why more and more westerners are starting to open their eyes to both the depravity of Israel and of their own government.

❖

Caitlin Johnstone on Twitter: "We're meant to accept that it's fine and normal for Israelis to hate the Palestinians they're murdering and oppressing so much that they cheer for their deaths, but it's outrageous and unforgivable that the Palestinians who are being murdered and oppressed hate them back. https://t.co/4WxwNMea7k / Twitter"

We're meant to accept that it's fine and normal for Israelis to hate the Palestinians they're murdering and oppressing so much that they cheer for their deaths, but it's outrageous and unforgivable that the Palestinians who are being murdered and oppressed hate them back. https://t.co/4WxwNMea7k

❖

Israel apologia is the world’s worst people defending the world’s worst actions. You’re more likely to support Israel if you’re a shitty person, and if you weren’t a shitty person to begin with you’ll eventually have to turn into one to continue supporting Israel’s actions.

❖

Most Israel supporters are non-Jews, but when you talk about what awful people Israel supporters are they’ll try to claim you’re talking about Jews. Israel apologists who aren’t even Jewish will accuse you of anti-semitism for saying things that are really about them.

❖

Any time there’s a bombing campaign by the US-aligned power structure you see attempts being made to spin the civilians it kills as imperfect victims, and you’re seeing that with Gaza too.

The problem here is that there’s no way to spin children as imperfect victims; they are inherently blameless. If everyone in Gaza was a Hamas fighter, or even a military-aged male, then the “imperfect victims” strategy would work fine, but Gaza happens to contain an unusually high percentage of children and Israel is killing them at a very unusual rate. You can try to say babies and small children are actually covert Hamas fighters or Hamas supporters, but all you’ll succeed in doing is making your side look worse than it already does. It’s a major obstacle for the western empire.

_____________

My work is entirely reader-supported, so if you enjoyed this piece here are some options where you can toss some money into my tip jar if you want to. Go here to buy paperback editions of my writings from month to month. All my work is free to bootleg and use in any way, shape or form; republish it, translate it, use it on merchandise; whatever you want. The best way to make sure you see the stuff I publish is to subscribe to the mailing list on Substack, which will get you an email notification for everything I publish. All works co-authored with my husband Tim Foley.

Bitcoin donations: 1Ac7PCQXoQoLA9Sh8fhAgiU3PHA2EX5Zm2

Featured image via Wikimedia Commons.

War Is Not Abstracted Anymore

Listen to a reading of this article (reading by Tim Foley):

https://medium.com/media/ceb114b202032f44363cdcdf750d0794/href

Pentagon contractor Elon Musk and war criminal Benjamin Netanyahu had a conversation that they broadcast on Twitter during Musk’s apology pilgrimage to Israel in a desperate bid to salvage his public image amid costly accusations of antisemitism.

The “conversation” was really more of a monologue, with the Israeli leader droning on in his conspicuously American accent while Musk meekly agreed with him on every point. During his lecture, Bibi said something worth highlighting while complaining about the worldwide pro-Palestine protests that have been underway since the beginning of Israel’s ongoing Gaza massacre.

“We have mass demonstrations,” Netanyahu said at around the 15:55 mark. “Where were these demonstrations when over a million Arabs and Muslims were killed in Syria, in Yemen, many of them starving to death, those who didn’t die in explosions. Where were the demonstrations in London? In Paris? In San Francisco? In Washington? Where are they?”

“The answer is they don’t care about the Palestinians, they hate Israel,” Netanyahu said. “And they hate Israel because they hate America.”

Benjamin Netanyahu - בנימין נתניהו on Twitter: "https://t.co/vJDbprlHhj / Twitter"

You hear this “where were the protests over Yemen and Syria?” talking point over and over again from Israel apologists, the argument essentially being that because few people protested the mass killings in those countries then Israel should get to do a little genocide of its own, as a treat.

This talking point is stupid for a few reasons, including the way it tends to avoid the inconvenient fact that the bloodshed in both Yemen and Syria was facilitated by US interventionism, just like the bloodshed in Gaza is. The civil war in Syria was only able to occur because the western alliance and its regional partners flooded the nation with weapons given to extremist factions in the hope of toppling Damascus, and Saudi Arabia’s war crimes in Yemen were fully backed by the US and its allies.

The talking point is also stupid because there are many entirely legitimate reasons the Gaza massacre is getting special attention. In a recent New York Times article titled “Gaza Civilians, Under Israeli Barrage, Are Being Killed at Historic Pace,” Lauren Leatherby explains that Israel’s actions in Gaza are actually quite different from other conflicts this century, killing far more civilians far more rapidly than the wars in places like Syria and Ukraine. Last week the UN’s emergency relief coordinator Martin Griffiths said during a CNN interview that Gaza is the worst humanitarian crisis he’s ever seen, even worse than the Killing Fields in Cambodia. This conflict is being treated differently because it is different.

Another reason this specific bombing campaign is getting so much more public backlash than others is because the pro-Palestine movement has had generations to build, whereas when the west lays waste to a country using military explosives it’s normally a fast ordeal which moves from manufacturing consent to execution very quickly. By the time people figure out they were lied to about the justifications for a depraved war the empire is usually two or three new wars down the track. The Israel-Palestine issue has been just sitting there for decades, so there’s been time to accumulate popular opposition. Once someone learns about the realities of the Palestinian plight they very seldom abandon their support for it, so every newly-opened pair of eyes stays open on this issue for a lifetime.

Caitlin Johnstone on Twitter: "I keep seeing this fuzzbrained argument. I've written more words than almost anyone else in the English-speaking world in opposition to the mass atrocities the US empire has caused in Yemen and Syria, and I write against the US-backed slaughter in Gaza for the exact same reasons. https://t.co/OtiQnZv40h / Twitter"

I keep seeing this fuzzbrained argument. I've written more words than almost anyone else in the English-speaking world in opposition to the mass atrocities the US empire has caused in Yemen and Syria, and I write against the US-backed slaughter in Gaza for the exact same reasons. https://t.co/OtiQnZv40h

But perhaps the dumbest thing about this talking point is the fact that it ultimately works against the agendas of the people saying it. Israel apologists keep asking “Where were the protests over Yemen and Syria,” and gradually the millions of people who are beginning to wake up to the criminality of the US-centralized power alliance as a result of the Gaza massacre are going to start asking themselves the same question.

Because the assault on Gaza is so uniquely horrific and is being broadcast onto people’s social media feeds in real time, millions of people around the world are being snapped out of the propaganda-induced coma that has had them consenting to evil war after evil war over the years. People are starting to realize they’ve been deceived about the Israel-Palestine conflict, and they’re starting to wonder what else they’ve been deceived about. Keep asking them “Where were the protests over Yemen and Syria,” and eventually they’re going to start researching those conflicts and learning about their own government’s role in them, and from there it’s only a matter of time before they start asking, “Hey yeah! Where WERE the protests over Yemen and Syria??”

In a new article for The Guardian titled “The war in Gaza has been an intense lesson in western hypocrisy. It won’t be forgotten,” Nesrine Malik writes that “for the first time that I can think of, western powers are unable to credibly pretend that there is some global system of rules that they uphold. They seem to simply say: there are exceptions, and that’s just the way it is. No, it can’t be explained and yes, it will carry on until it doesn’t at some point, which seems to be when Israeli authorities feel like it.”

Nesrine Malik on Twitter: "'The lesson from Gaza is brutal and short: human rights are not universal and international law is arbitrarily applied.' https://t.co/RcGEOp7JP0 / Twitter"

'The lesson from Gaza is brutal and short: human rights are not universal and international law is arbitrarily applied.' https://t.co/RcGEOp7JP0

“Part of that inability to reach for convincing narratives about why so many innocent people must die is that events escalated so quickly,” Malik adds. “There was no time to set the pace of the attacks on Gaza, prepare justifications and hope that eventually, when it was all over, time and short attention spans would cover up the toll. Gaza has been a uniquely, inconveniently, intense conflict… The area is so densely populated that the toll of civilians is too high, and evidence for having undermined Hamas’s capabilities, the only possible justification for the casualties, is too low.”

This is the sort of political moment in which newly-formed critics of the western war machine are being asked to think carefully about why there hasn’t been a robust resistance to their governments’ other criminal actions. Which looks like a nightmare waiting to happen for the propagandists whose job is to manufacture consent for depraved acts of war.

One thing the empire is about to realize is that the western public has lost all its appetite for war. All the careful sanitising, video-gamifying and propagandizing that has been put in place since Vietnam in order to build a platform of consent for “humanitarian” wars has cratered into nothing over the course of mere weeks.

You can’t have an up close and personal relationship with the reality of bombs and all the things they do to human flesh and then go back to the way you were ever again. Millions of western eyes have been changed forever.

“War” is not abstracted any more.

_______________

My work is entirely reader-supported, so if you enjoyed this piece here are some options where you can toss some money into my tip jar if you want to. Go here to buy paperback editions of my writings from month to month. All my work is free to bootleg and use in any way, shape or form; republish it, translate it, use it on merchandise; whatever you want. The best way to make sure you see the stuff I publish is to subscribe to the mailing list on Substack, which will get you an email notification for everything I publish. All works co-authored with my husband Tim Foley.

Bitcoin donations: 1Ac7PCQXoQoLA9Sh8fhAgiU3PHA2EX5Zm2

Featured image via Gaza Palestine (Public Domain)

Proportionality, Psychic Harm, and the Day After (guest post)

“Once we count psychic harm, it looks like Israel’s war might be proportional. But it could be proportional only if the Israelis aren’t imposing on basically all Gazans a greater psychic burden than the psychic burden that Israelis hope to avoid,” which could be the case “if Israel takes it upon itself, as soon as possible, to reassure the Gazans that Gaza will not only be rebuilt, better than before, but that it will be set free as part of a two-state solution.”

In the following guest post, Alec Walen, professor of law and philosophy at Rutgers University, discusses the significance of psychic harm—primarily the psychic harm of living in terror—for an adequate moral assessment of the Israel-Hamas conflict and for an understanding of what Israel should do in Gaza.

It is part of the ongoing series, “Philosophers On the Israel-Hamas Conflict“.

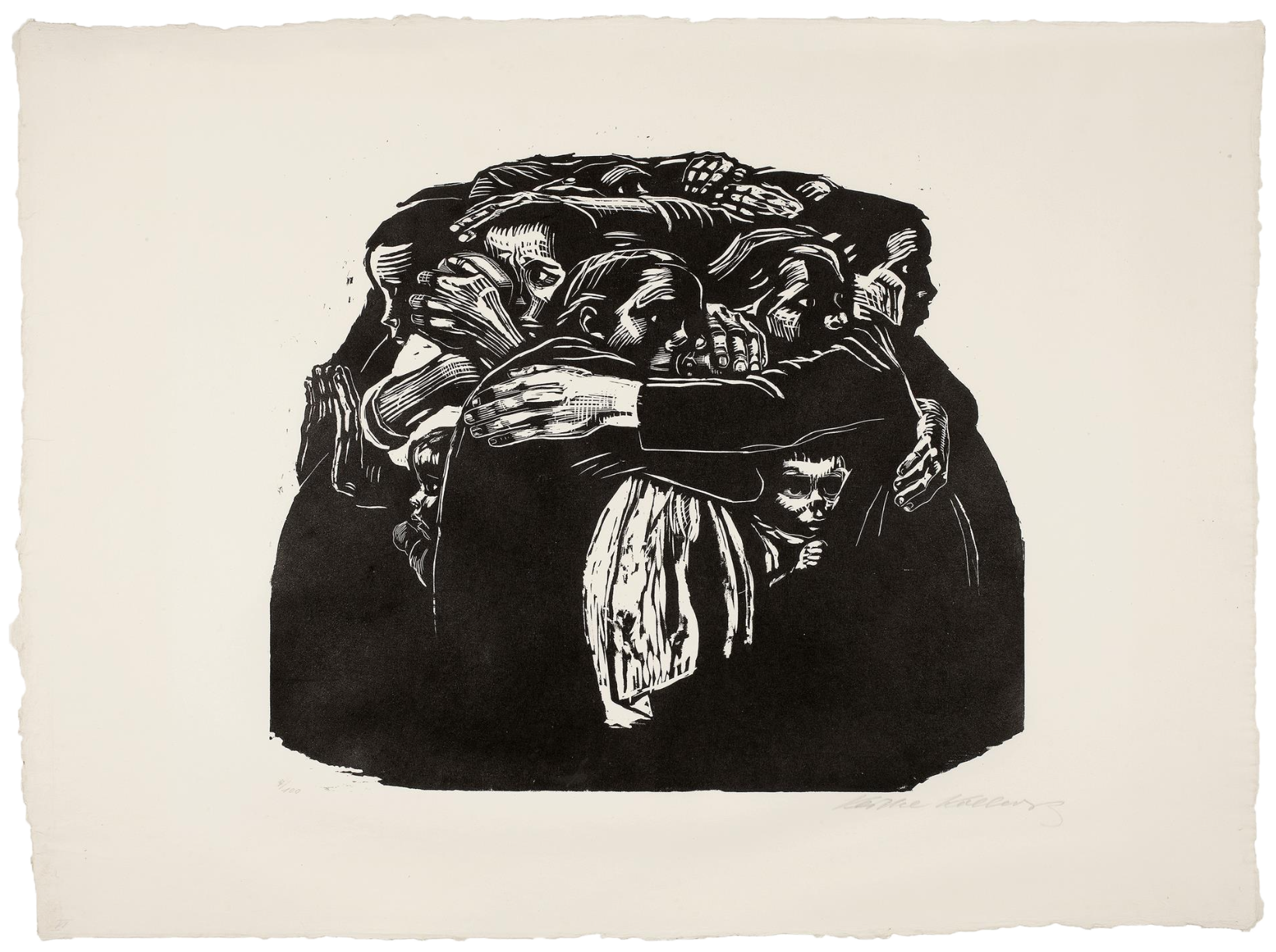

[Käthe Kollwitz, “The Mothers”]

Proportionality, Psychic Harm, and the Day After

by Alec Walen

As I write this, there is a pause in the fighting in Gaza, and it is not clear whether Israel will resume its efforts to depose Hamas. But it seems likely that it will. Thus, I want to address the question: Can it wage war to depose Hamas without causing disproportionate harm? By appealing to the idea of psychic harm, I want to argue that the answer is: Maybe. But of course, there is psychic harm on both sides, and for Israel’s war to avoid causing disproportionate damage, it will have to take proactive measures to ensure that the psychic harm in Gaza is minimized if and when it topples Hamas.

To be clear, I am discussing proportionality ad bellum, not in bello. I have no doubt that some of the innocent civilians Israel has killed in Gaza were killed in disproportionate attacks. Such attacks are to be condemned. But my concern is with the war as whole. Even if disproportionate attacks were the exception so far—a topic on which I remain agnostic for now—and even if Israel exercises maximal care for noncombatants from this point forward, we need to know if the overall amount of harm Israel would cause in deposing Hamas is proportionate to the good that would result from doing so.

If we count just the death toll on both sides, then I think Victor Tadros was right when he wrote in an earlier post that Israel’s “response is … already disproportionate.” On the one hand, if Hamas is left in power in Gaza, it would almost certainly regroup, rearm, and strike again. It might even be able to strike with a more deadly attack next time. But short of acquiring a nuclear weapon—which one assumes it would not want to use in land it wants to occupy—it is hard to see how it could cause more than a few thousand deaths in the foreseeable future. By contrast, Israel has already caused over 12,000 deaths in Gaza, most of whom, it seems fair to assume, are non-combatants. And if it continues until Hamas is fully removed from power in Gaza, it will have to kill thousands more. In addition, the toll of thirst, hunger, stress, displacement, poverty, and disease will surely kill multiples more. Suppose a reasonable estimate of the total death toll is approximately 30,000. Saving a few thousand lives from a potential attack cannot justify so many deaths. Deaths to deaths, Israel’s war is grotesquely disproportionate.

But deaths are not all that matter. Psychic harm matters too. Hamas has shown that it is undeterrable. Thus, if Hamas remains in power, it seems likely that it is only a matter of time until it attacks again. Living with that terror is a significant tax on the souls of Israelis, and this should count in the proportionality balance. Of course, as already noted, the psychic harm on Gazans should count too. But I want to start with the Israeli appeal to psychic harm to show how it could make the war proportional.

The thesis that more abstract harms can be relevant to proportionality was the subject of work by Thomas Hurka in 2005, and by David Rodin, Cecile Fabre, and Jeff McMahan in a collection published in 2014. The focus of these discussions was the possibility of invasions that did not impose concrete harms like death, torture, and rape, but more abstract harms like taking territory or undermining sovereignty. The latter three philosophers were more skeptical than Hurka of the idea that the prevention of such abstract harms could justify killing. But even if they are correct, I think there’s an important middle position between killing, raping, and torturing, on the one hand, and interfering with territory and self-governance, on the other. And I think living in a protracted, well-grounded state of fear that one or the people that one cares about will be killed in an attack counts for that middle state. The fear need not be that one will likely be killed. The fear need only be a source of ongoing significant trauma, based in the thought that a substantial group of people just a few miles away are plotting and building the capacity to carry out a brutal attack that could target anyone in the country and that will likely kill thousands.

Of course, one person cannot justifiably kill another as collateral damage to prevent herself from having to live in a state of traumatizing fear. But I think numbers matter when the harms are close enough in magnitude to be “relevant.” Indeed, I think that if we look into why preventing torture and rape count as reasonable bases for using lethal force, we see that it’s not just the momentary horrible experience and violation that matter; it’s the ongoing psychological damage such experiences impose on people. This sort of trauma can add up so that if enough people face it, then it will be proportional to cause a lesser number of deaths to innocent people if that is an unavoidable side-effect of preventing that amount of serious psychological harm.

Could this apply to make Israel’s war on Hamas proportional? There are roughly seven million Jews living in Israel now most of whom seem to feel—based on my own informal discussions with Israelis—that living with Hamas operating on its border is “intolerable.” I interpret that to mean that the sense of insecurity it induces in them gives them a good reason to wage war on Hamas, aiming to depose it. To take that idea seriously, we have to suppose that they think that avoiding that insecurity is important enough to justify causing the collateral damage that will come from deposing Hamas. If we assume that will be around 30,000 deaths, then the implicit ratio the Israelis are invoking is something like one collateral death for every 200 Israelis who would otherwise live in a state of profound insecurity. That number needs to be adjusted, however, for those Gazans who will necessarily, no matter how the war ends, carry a similar, if not greater, psychic burden because of the war. Those who lost loved ones in the war presumably fit this description. Let us assume ten Palestinians will carry that burden for every Palestinian who is killed. Let us add to that the number who are injured and who will carry that burden for the rest of their lives. Suppose that number is five times higher than the number killed. If we add those numbers together, we get about half a million. If we offset the number of Israelis with a claim to avoid a psychic burden by that number, the number of Israelis whose psychic burden counts will still be close to six million. The ratio would still be something like one collateral death for every 200 or so Israelis who would otherwise live in a state of profound insecurity. I find that I cannot reject that as an unreasonable balance. In other words, once we count psychic harm, it looks like Israel’s war might be proportional.

But it could be proportional only if the Israelis aren’t imposing on basically all Gazans a greater psychic burden than the psychic burden that Israelis hope to avoid. But isn’t it clear that this war is in fact imposing a greater psychic burden on basically all Gazans? There are currently over two million people living in Gaza, and given the death, destruction, and displacement caused by the war, it would seem crazy to suggest that the war has not caused more psychic harm to those two million people than it might alleviate for Israelis. This would seem to negate the potential for Israelis to appeal to psychic harm to make their war proportional.

There is a possible response to this objection, but before getting to it, I want to address two objections to the idea that Israel can cite the psychic harm from the threat of Hamas on its side of the balance.

One objection to this argument is that to live in Israel is to live with such threats. Hamas is not the only threat. Hezbollah too would like to wipe Israel from the map. So would various other groups, including the Iranian regime. Israel cannot possibly eliminate these threats, so it should not be allowed to cite the extra threat from Hamas as a reason to kill Gazans.

To me the most important response to this objection is this: To live with a neighbor who wants to destroy you is bad enough, but to live with a neighbor who is undeterrable is much worse. For an analogy, consider the difference between living in a city with an ex who you know wants to hurt you, but who you think is also deterred by the threat of criminal punishment from doing anything crazy, and living in a city with an ex who you know is so committed to doing you harm that no threat of punishment will deter him. The other powers all seem, so far at least, deterred by the power of Israel (backed up by the U.S.). For Hamas, this is not the case.

Another objection is that there is no need to get to the issue of proportionality because the necessity condition is not met. It is not met because there are less harmful ways to reduce the terror from Hamas. It can either be degraded or contained.

The response to this objection is that it seems false. Israel has degraded Hamas, killing or imprisoning its fighters or leaders before, and it has come back stronger. And it has tried containing it too. It has had a blockade in place since 2007, aimed at preventing Hamas from arming itself; the attack of Oct. 7 showed that the blockade failed. And even if better border security might have contained that attack, making this war unnecessary, Hamas can learn from past mistakes and find new ways to attack. It is not unreasonable to think that Hamas must be deposed for Israel to prevent it from attacking again.

So let us return to the issue of the psychic harm the Israelis are causing by waging this war. How could the misery the war is inflicting on Gazans not fully offset the psychic gains for the Israelis? The answer is that it could count for less if, for most Gazans, it is much more short-lived psychic pain than that which the Israelis would otherwise suffer. But the only way for it to be much more short-lived is if Israel takes it upon itself, as soon as possible, to reassure the Gazans that Gaza will not only be rebuilt, better than before, but that it will be set free as part of a two-state solution. The alternative, in which Israel simply goes back to occupying Gaza, imposing daily humiliations on the Palestinians, would leave the Gazans with at least as much psychic burden as that which the Israelis seem to want to cite to justify their war.

The current Israeli government, stocked with genocidal extremists, could not possibly offer the Palestinians a reasonable two-state solution. But Netanyahu is now deeply unpopular in Israel. If, the day after the war, Israel can rid itself of this government and install a better one, one that is committed to respecting the lives and psychic needs of Palestinians as well as Israelis, it may be able to salvage the justifiability of this war (at least in terms of proportionality).

No reasonable person thinks a two-state solution will be easy to achieve. Neither the Palestinian nor the Israeli public seems to be in favor of it. Hamas is now more popular than ever among the Palestinians, because it fights for their dignity. And while some Israeli governments in the past have proposed a two-state solution, it seems that they never had a popular mandate to do so. But war can change things, making viable options that were once impossible. Israeli citizens should seize this opportunity to change course and make good faith efforts to establish a two-state solution, and outside powers that have some influence in the region should do what they can to pressure Israel to pursue that path towards peace. If it does, it may find Palestinian partners. But if does not, then it deserves condemnation for waging a disproportionate war.

The post Proportionality, Psychic Harm, and the Day After (guest post) first appeared on Daily Nous.