Time

Banking the Most Valuable Currency: Time

David Gill might be the richest man in Sebastopol, California. The semi-retired health care administrator is banking the most valuable currency in the world: time. Gill currently has 480 hours in his savings account at the local time bank, “and I haven’t even registered any of my hours in 2023,” he says.

In brief, a time bank does with time what other banks do with money: It stores and trades it. “Time banking means that for every hour you give to your community, you receive an hour credit,” explains Krista Wyatt, executive director of the DC-based nonprofit TimeBanks.Org, which helps volunteers establish local time banks all over the world. Nobody keeps track of the exact number, but thousands of time banks with several hundred thousand members have been established in at least 37 countries, including China, Malaysia, Japan, Senegal, Argentina, Brazil and in Europe, with over 3.2 million exchanges. There are probably more than 40,000 members in over 500 time banks in the US.

Steve Bursch (with red rake) and fellow time bankers beautify the library grounds for the City of Sebastopol. Credit: Marty Roberts / Sebastopol Area Time Bank

Steve Bursch (with red rake) and fellow time bankers beautify the library grounds for the City of Sebastopol. Credit: Marty Roberts / Sebastopol Area Time Bank

In Sebastopol, 250 residents have time bank accounts where they save and withdraw hours as needed. For instance, Gill, who is also the main local time bank coordinator, likes to offer his expertise with computer programming, editing and financial planning. In return, he asks for help when he needs a ride to the airport or someone to transport heavy furniture. He rattles off the first few of many examples: “Steve, who lives on the next block, drove me and my partner to the Santa Rosa airport. Ken fixed the icemaker in our refrigerator, and Elaine did some electrical work.”

If he had called professional repair and taxi services, the expense would have been significant. However, the interest, so to speak, goes beyond the value of a mere transaction. The time banks are building social capital. “I’ve made wonderful friends I wouldn’t have met otherwise and we now invite each other to our garden parties,” says Gill. “It’s about making community and being a part of the community. You can’t put a price on that stuff.”

David Gill came to the time bank like most of his neighbors. He doesn’t remember where he first heard about it a few years ago, but he immediately thought it was a great idea. He signed up, started using it, and when the founders asked for help, he stepped up. He gets paid in the currency he values most: hours.

Many time banks are volunteer community projects, but the one in Sebastopol is funded by the city and operates under the nonprofit status of the Community Cultural Center. After all, time is money. “Every volunteer hour is valued around $29,” Wyatt calculates. “Now think about the thousands of dollars a city saves when hundreds of citizens serve their community for free.” The Sebastopol time bank has banked more than 8,000 hours since its launch in 2016. Members might reimburse each other for costs — for instance, gas mileage or materials — but the service itself and the membership are always free.

Time bank members in the Netherlands participate in a DIY electronics course. Credit: Timebank.cc

Time bank members in the Netherlands participate in a DIY electronics course. Credit: Timebank.cc

Some cities look to time banks as a model to support an aging population. In St. Gallen, Switzerland, only members over the age of 50 may join the local Stiftung Zeitvorsorge, or “Foundation Time Care,” which was founded in 2011 and has 320 members who have banked more than 80,000 hours. While Sebastopol’s time bank is more geared toward practical services to fill a gap other community services don’t address, members in St. Gallen regularly help seniors run errands, shop for groceries, take them to the doctor or simply keep them company. Here, too, the city guarantees the program, hoping that it will help seniors to stay in their homes and live independently longer because 75 percent of locals said in a poll that they hoped to stay in their homes as long as possible. Even if only five people were enabled to enter care homes a year later, the foundation’s executive director Jürg Weibel recently told the German magazine Der Spiegel, the investment would have already recouped itself. “The reality is that grown-up kids live in other areas,” Weibel said. “Also, many seniors are consciously looking for a new purpose.”

The time banks in both Sebastopol and St. Gallen have more offerings than demand. In a way, they have too much time in the bank, not least because seniors are looking to get help later in life.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.

[contact-form-7]

“Seniors have a lot to offer,” Gill believes. While he points to his white hair as “pretty representative of the age of our time bank members,” some universities and schools have established time banks specifically for students and teachers at their institutions.

The idea of time as a bankable currency goes back to a Japanese seamstress and activist, Teruko Mizushima, who traded her sewing skills for fresh vegetables during the Pacific War in the early 1940s. In 1973, she started the first “Volunteer Labour Bank” that soon included thousands of members.

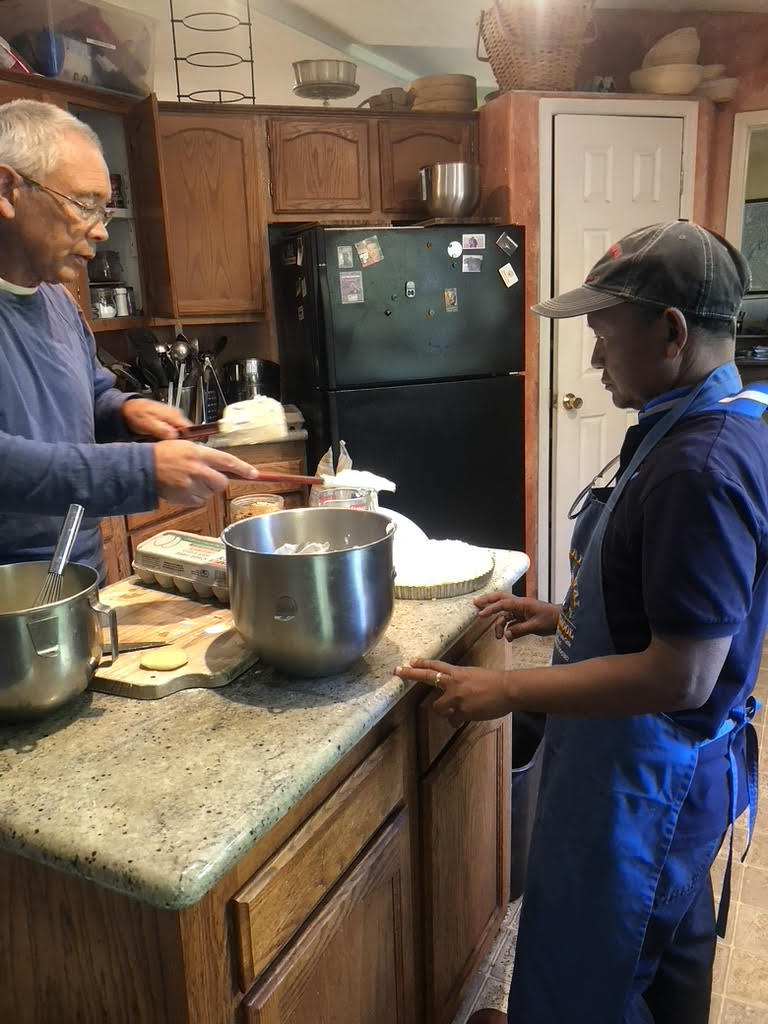

Tong Ginn (left) teaches Jesuda “Wee” Simla how to make croissants. Credit Michael D. Fels / Sebastopol Area Time Bank

Tong Ginn (left) teaches Jesuda “Wee” Simla how to make croissants. Credit Michael D. Fels / Sebastopol Area Time Bank

In the US, the civil rights lawyer Edgar Cahn, who worked as a speechwriter for Robert F. Kennedy and executive assistant to Peace Corps founder Sargent Shriver, rediscovered the idea of time banks as allies to fight poverty in the early 1960s, when money for social programs had dried up. He later coined the term “Time Dollars” and trademarked “Time Bank.” In 1995, he founded the nonprofit Krista Wyatt now works for as a hub of resources, first under the name “Time Dollar Institute.” “When he was bedridden in a hospital after a severe heart attack, he felt ‘useless,’ and saw time banks as a way for everyone to contribute to the community, no matter their age or qualifications,” Wyatt explains.

Cahn formulated five core principles that guide time banks to this day: First, everyone has something to contribute. Second, valuing volunteering as “work.” Third, reciprocity or a “pay-it-forward” ethos. Fourth, community building, and fifth, mutual accountability and respect.

“What captured me is that people are doing things out of their own good heart,” Wyatt says. “Many years ago, a woman got really upset because, as she said to Edgar Cahn, ‘I have nothing to give.’ Edgar Cahn listened and finally responded, ‘You have love to give.’ And the whole room just went silent.”

Every hour of service is valued the same, no matter how much skill and expertise a task takes, whether it’s an hour keeping someone company, helping them file their taxes or repair a roof. Through a simple online platform, every member can offer and request services and then register the hours they served or received. Especially during and since the Covid pandemic, the bank has also been an antidote to the epidemic of loneliness. For instance, the Sebastopol time bank regularly hosts in-person events and meetings.

Lathrup Village, Michigan time bank members doing yard work together. Credit: Michigan Municipal League

Lathrup Village, Michigan time bank members doing yard work together. Credit: Michigan Municipal League

“We do events where everybody brings a list of five things they need to get done,” Wyatt gives an example. “You wouldn’t believe how many things get crossed off these lists in a room full of people who are willing to help.”

Wyatt came to TimeBanks after supporting cancer survivors. She’d read Cahn’s 2000 book, No More Throw-Away People, and was looking for a way to give back. “There are people like me who like to work on the computer rather than cleaning my garage,” Wyatt says, “and there are people who’d rather clean a garage than be stuck behind a computer. Everybody can be part of the time bank community. It’s as simple as that.”

In a way, time banks are the 2.0 version of what used to happen organically in small communities: Neighbors and colleagues would help each other out. “Now we simply do it with the help of a computer,” Gill says. “Or you may just pick up the phone and call another member directly rather than post a request online. It helps to get to know the various members.”

Artist Elizabeth “Liz” Newton with David Gill’s repaired and mosaic toilet tank cover. Credit: David Gill / Sebastopol Area Time Bank

Artist Elizabeth “Liz” Newton with David Gill’s repaired and mosaic toilet tank cover. Credit: David Gill / Sebastopol Area Time Bank

While the core principles are simple, both Wyatt and Gill acknowledge that implementing and managing the time bank well is a complex task. They both spent countless hours trying out different software programs before settling on a program that works well for them.

Wyatt dreams of connecting the various time banks internationally so that someone in, say, San Francisco, could learn French with a time bank member in Paris. Or a tourist traveling in Japan could meet local time bank members there and, after her return, show other tourists around her own town.

Interpreted this way, the time credit functions as an alternative currency. Members can also donate their services to community members in need and the community without banking a credit for themselves.

For instance, in Sebastopol, artist Ellie Kilner completed a giant sculpture at the Sebastopol Senior Arts Center and other art projects with the support of fellow time bank members.

Become a sustaining member today!

Join the Reasons to be Cheerful community by supporting our nonprofit publication and giving what you can.

Gill’s favorite exchange, so far, also has to do with art and with a broken toilet cover. Because the toilet was an ancient model, it was impossible to find a replacement. He posted a request for help on the time bank’s online platform, and a local mosaic artist not only glued the broken pieces together but turned it into a colorful piece of art. “Now it’s a conversation piece!” Gill raves. He says he plans to request more work from this artist, Elizabeth Newton.

He is clearly passionate about his role in facilitating the time bank and everything that time banks can provide: “I don’t think we can ever have too many friends or too much community.”

The post Banking the Most Valuable Currency: Time appeared first on Reasons to be Cheerful.

Women’s Economic Empowerment and Control over Time in Sub-Saharan Africa (Nov 1-2)

November 1–November 2, 2021

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent losses in lives and livelihoods are looming over Sub-Saharan Africa. As in the rest of the world, the pandemic has exposed the enduring inequalities and injustices in stark terms, including those based on gender and those intersecting with gender, such as economic deprivation. There is a growing realization that collective action to overcome the long-term and ongoing challenges requires greater engagements between researchers, civil society organizations, and policymakers. Accordingly, we are organizing a two-day virtual workshop that will feature research and policy discussions that address economic aspects of gender inequalities in Sub-Saharan Africa from various angles. Part of the research to be presented is work conducted by scholars at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College in collaboration with scholars from Sub-Saharan Africa with the generous support of the Hewlett Foundation. The workshop will also highlight recent research by leading scholars in the region. The presentation of research will be accompanied by a free-wheeling exchange of ideas between scholars and participants. A policy roundtable with a select group of prominent members of the academic, policymaking, and civil society communities will conclude the workshop.

The workshop will be held between 13:00 and 15:30 (GMT) on November 1, 2021 and between 13:00 and 16:00 (GMT) on November 2, 2021.

This event is free and open to the public.

The complete schedule and information for participants is available below:

Participation Instructions

The workshop will be hosted on Zoom. Please use the following links to participate:

November 1

https://bard.zoom.us/j/81117573608?pwd=Z3gyaXlkY0pSSkpGY1JHQlBNQmt5UT09

November 2

https://bard.zoom.us/j/88110321894?pwd=TWFiTnVPUklzN0VLWm5uQ0JUNm81Zz09

Program

GMT

EDT

13:00–15:30

9:00–11:30

Day 1: Women’s Decision-making Power and Patriarchal Structures in Sub-Sharan Africa

Welcome and Overview

Dimitri Papadimitriou, Levy Economics Institute

Luiza Nassif Pires, Levy Economics Institute

Measuring Patriarchy: Meso-level Variations in the Strength of Patriarchy in Sub-Saharan Africa

Ajit Zacharias, Levy Economics Institute

Fernando Rios-Avila, Levy Economics Institute

Women’s Decision-making Power in Ghana

Thomas Masterson, Levy Economics Institute

Discussant: Nkechi Owoo, University of Ghana

Discussant: Beatrice Kalinda Mkenda, University of Dar es Salaam

Q&A

Closing Remarks

Thomas Masterson, Levy Economics Institute

Day 2:

13:00–14:05

9:00–10:05

Session 1:

Opening Remarks

Ajit Zacharias, Levy Economics Institute

Asset Ownership and Egalitarian Decision Making Among Couples: Some Evidence from Ghana

Abena Oduro, University of Ghana, Legon

Nthabiseng Moleko, University of Stellenbosch

Women Economic Empowerment in East Africa: Policy and Practice Focus on Ethiopia (Oxfam Program)

Ankets Petros, Oxfam Ethiopia

Q&A

14:15–15:55

10:15–11:55

Session 2: Policy Roundtable: Challenges in Achieving Women’s Economic Empowerment

Opening Remarks

Chalachew Getahun Desta, Center for Population Studies, Addis Ababa University

Flora Myamba, Women and Social Protection, Tanzania

Sadou Doumbo, Demographic Dividend National Observatory, Ministry of Economy and Finance, Mali

Patricia Blankson Akakpo, Network for Women’s Rights in Ghana

Mamadou Bobo Diallo, UN Women

Q&A

15:55–16:00

11:55–12:00

Closing Remarks & Thank Yous

Thomas Masterson, Levy Economics Institute

Biographies

Patricia Blankson Akakpo is a Programme Manager of the Network for Women’s Rights in Ghana (NETRIGHT) – a women’s rights and economic justice advocacy network. Patricia holds a BA in political science with philosophy; MA in development studies with specialization in human resources and employment; and gender studies; and a diploma in development leadership. Patricia joined NETRIGHT in 2003. She has over twenty-five years of experience in gender and development in Ghana working with women and vulnerable groups, young women collectives, and women’s rights organizations (WROs). Patricia is a past cochair of CPDE representing the feminist sector and currently the Africa regional coordinator for CPDE’s Feminist Group (CPDE Africa FG).

Chalachew Getahun Desta (Ph.D. in socioeconomic development planning and geography) is assistant professor of population studies, socioeconomic development planning, geography, and environment at the Center for Population Studies (College of Development Studies, Addis Ababa University). He teaches courses on human geography (including population, economics, and urban and regional geographies), population and development, and research methods. His areas of research interest include women, fertility, and household well-being (maternal labor force participation, maternal time allocation, consumption); urbanization, rural–urban migration, employment, and the informal sector; forced migration, refugees, and internally displaced persons; labor migration, diasporas, and return migrants; and population, resources, and the environment.

Mamadou Bobo Diallo is an economics specialist on macroeconomics, in the economic empowerment section at UN Women. Bobo’s areas of focus include capacity development/technical support and research on gender, macroeconomics, gender-based inequalities, poverty, the care economy, and social protection. Prior to joining UN Women, he was an actuarial analyst for Manulife Financial in Boston, a research fellow at the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis in New York, a macroeconomics consultant for two with the World Bank’s Governance and Public Policy Division, a policy specialist for UNDP Regional Bureau for Africa in New York, and an economic affairs officer with the UN Economic Commission for Africa in Ethiopia. Bobo holds a bachelor of science degree in mathematics from Salem State University (Boston) and a Ph.D. in economics, with a focus on development, growth, and econometrics from the New School for Social Research (New York City, NY).

M. Sadou Doumbo is the general director of the National Demographic Dividend Observatory in Mali and the coordinator of the national transfer accounts (NTA) team. He is also involved in doctoral studies based on the lifecycle deficit financing (Generational Economy Regional Research Centre and Centre de recherche en Economie et Finance Appliquée / Université de Thiès).

With about 15 years’ experience in development planning activities in several structures such as the ministry of development planning and UNFPA, M. Doumbo developed great competencies in advocacy and communication for the integration of population and demographic issues in national policies, strategies, and demographics. Since 2015, he has participated in the definition and monitoring of the Sahel Women Empowerment and Demographic Dividend project (SWEDD). He is very involved, as a resource person, in several national and international population and development frameworks, working with UNFPA, PRB, and UNECA, among others, to highlight the need to invest in youth, girls, and women.

Thomas Masterson is director of applied micromodeling and a research scholar in the Levy Economics Institute’s Distribution of Income and Wealth program. He has worked extensively on the Levy Institute Measure of Well-being (LIMEW), an alternative, household-based measure that reflects the resources the household can command for facilitating current consumption or acquiring physical or financial assets. With other Levy scholars, Masterson was also involved in developing the Levy Institute Measure of Time and Income Poverty (LIMTIP), and has contributed to estimating the LIMTIP for countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. He has also taken a lead role in developing the Levy Institute Microsimulation Model.

Masterson’s specific research interests include the distribution of land, income, and wealth, with a focus on gender and racial disparities. He has recently published articles in The Review of Black Political Economy and The Journal of Economic Issues. He holds a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Beatrice Kalinda Mkenda is a senior lecturer and acting dean of the School of Economics at the University of Dar es Salaam. She has a Ph.D. in economics from Göteborg University in Sweden. She teaches international economics and macroeconomics at both postgraduate and undergraduate levels.

Prior to joining the University of Dar es Salaam, she worked as lecturer at the University of Zambia, and later worked as a research fellow with the Economic and Social Research Foundation (ESRF) under the “Globalization in East Africa” project. She participated in teaching a postgraduate diploma course in poverty analysis that was jointly offered by the International Institute of Social Studies (Erasmus University), Research on Poverty Alleviation (REPOA), and ESRF.

Her recent research has looked at diverse areas such as indigenous knowledge and employment generation among women; empowering women in tourism micro, small, and medium enterprises; determinants and constraints of women’s sole-owned tourism micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in Tanzania; why it is imperative for Tanzania to industrialize; informal sector employment; regional integration for accelerating industrialization in Tanzania: opportunities and challenges in the East African community; and ability of SMEs to penetrate export markets. She is currently working on a joint research proposal to examine the gendered impact of food safety compliance: the case of Tanzania and Uganda’s exports to the EU market.

Nthabiseng Moleko is a development economist who is a core faculty member at the University of Stellenbosch Business School (USB) where she teaches economics and statistics as a senior lecturer since 2017. She also serves as a commissioner for the Commission for Gender Equality appointed by the president in 2017 and is currently the deputy chairperson of the commission. She completed her Ph.D. in development finance at USB on pension funds and national development and is the first South African woman to be conferred a doctorate in this discipline. Dr. Moleko regularly appears on various network’s programming on economic and business coverage as a thought leader.

Flora Myamba is a senior specialist on social protection and gender based in Tanzania. She has consulted for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Center for Global Development, UN Agencies, EU-OECD, World Bank, and Government of Tanzania, among others. Flora is a master trainer for the African Union–owned TRANSFORM Training for Social Protection Floors. She earned her doctorate from Western Michigan University, and has published in local and reputable international journals including Oxford Development Studies, Cambridge University Press, Global Social Policy, and African Development Review. She is currently leading a project on gender, financed by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and collaborating with the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College on a study on women’s economic empowerment and control over time, among other works.

Luiza Nassif Pires is a research fellow working in the Gender Equality and the Economy program at the Levy Institute. Her research interests include gender and political economy, distributional aspects of gender discrimination, gender and racial aspects of development, and input-output methods. Her recent research relies on statistical equilibrium and game theory to formalize the impacts of gender and racial segregation in the labor movement with an application to the United States. Nassif Pires has also written on intersectional political economy with a focus on the impacts of social conflict for the labor theory of value and the long-run profit rate. She is also collaborating with Prof. Katherine Moos at University of Masschusetts, Amherst on a feminist input-output project.

Nassif Pires has taught microeconomics, macroeconomics, and political economy at the New York City College of Technology and at the Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts at The New School for Social Research. She holds a BS and MS in economics from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and a Ph. D. in economics from The New School for Social Research.

Abena D. Oduro is associate professor in the department of economics and is currently director (Ghana) of the Merian Institute for Advanced Studies in Africa (MIASA) at the University of Ghana, Legon. Her current research interests are in the areas of unpaid household work, poverty, inequality and vulnerability analysis, gender-responsive budgeting, and African regional integration. She is associate editor of Feminist Economics and a member of the International Association for Feminist Economics.

Nkechi S. Owoo is a senior lecturer at the department of economics at the University of Ghana. She is also a research associate with the African Centre of Research on Inequality Research (ACEIR) and a senior research fellow at the Environment for Development institute. Dr. Owoo’s research focuses on spatial econometrics in addition to microeconomic issues in developing countries, including household behavior, health, agriculture, gender issues, and population and demographic economics. Her current research focuses on the effects of the internalization of patriarchal attitudes by women and male partners on women’s labor market outcomes in Nigeria. Dr. Owoo received her BA in economics from the University of Ghana in 2006 and received a master’s degree in Economics from Clark University in 2009. She completed her Ph.D. in Economics from Clark University in 2012.

Ankets Petros has over 15 years of work experience in the development sector in Ethiopia. She holds an MA in sociology and BA in political science and international relations from Addis Ababa University.

Ankets has worked with Oxfam Ethiopia since 2016 as a gender specialist and currently in the capacity of gender program manager since 2019. She is responsible for developing and managing women’s empowerment projects, providing technical support to mainstream gender in Oxfam programs (humanitarian and long-term development) and specifically leading an influencing project called we-care (women economic empowerment and care).

Before joining Oxfam, Ankets worked with Consortium of Christian Relief and Development Associations (CCRDA) for two years as a networking and partnership senior officer overseeing more than 350 local and international NGOs who are members in the association in Ethiopia. She has also worked in policy engagement roles as gender program officer in ActionAid Ethiopia, engaging in designing and implementation of various women’s empowerment projects at the grassroots and regional levels.

Fernando Rios-Avila is a research scholar working on the Levy Institute Measure of Economic Well-Being under the Distribution of Income and Wealth program. His research interests include labor economics, applied microeconomics, development economics, and poverty and inequality.

As a doctoral candidate at Georgia State University, Rios-Avila worked as a graduate research assistant to Felix Rioja, and interned in the research department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, working under the supervision of Julie L. Hotchkiss. He formerly served as a researcher at the Social and Economic Policy Unit (UDAPE)—a government advisory unit and public policy think tank in La Paz, Bolivia—on issues of development, impact evaluation, and social expenditure, with an emphasis on children’s welfare. His research has been published in The Review of Income and Wealth, Industrial Relations, Southern Economic Journal, Applied Economics Letters, Stata Journal, and Business and Economics Research.

Rios-Avila holds a Licenciatura in economics from the Universidad Católica Boliviana, La Paz; an advanced studies program certificate in international economics and policy research from Kiel University; and a Ph.D. in economics from the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies at Georgia State University.

Ajit Zacharias is a senior scholar and director of the Levy Institute’s Distribution of Income and Wealth program. His research primarily focuses on the theory, measurement, and analysis of economic well-being and deprivation.

Along with other Levy scholars, Zacharias has developed alternative measures of economic welfare and deprivation. The Levy Institute Measure of Economic Well-Being (LIMEW) offers a framework that accounts for how changes in labor markets, wealth accumulation, government spending and taxes, and household production shape the economic determinants of standard of living. Levy scholars have utilized the LIMEW to track trends in economic inequality and well-being in the United States. The Levy Institute Measure of Time and Income Poverty is aimed at revealing the nexus between income poverty and unpaid work. This measure has been applied to the study of poverty in several Latin American countries, Turkey, South Korea, Tanzania, and Ghana.