Australian male violence against women: what the statistics say (and media should report)

Amid Australia’s justified concern over male violence against women, it seems worth keeping in mind our achievements. Femicide, in particular, has more than halved in the past three decades.

Prologue: Violence against women is a bad thing, and it’s still bad even when, as the article below points out, it used to be far worse. We should be trying hard to lower rates of violence, by finding good solutions and implementing them with urgency. As part of this, we should understand just what we’re dealing with – which is what this summary tries to do.

The issue of violence against women is in the news right now. Here’s a short summary of what we know about the issue in Australia.

- Before we say anything else, we need to acknowledge this: a really accurate picture of violent crime is hard to draw. Of the several factors clouding our vision, one stands out: most police-gathered crime figures are very unreliable. That goes double for violence against women. We can’t just hang that on the police, either: many crimes never get reported, or the police don’t find enough evidence to charge anyone, or judges and juries don’t convict. And all of these things change over time, as society changes.

- It’s hard to exaggerate what a problem this data unreliability poses when we try to find out about crime. My strong impression is that most of the public and many commentators expect official crime statistics will tell us everything we need to know. They never do.

- How bad is the problem? One typical analysis claims that “about 70% of domestic violence is never reported to the police.” You can probably come up with plenty of reasons why this figure is so high.

- Rates of reporting, charging and convicting thus affect the figures far more than do underlying changes in the actual level of violence in Australia.

- The result of all that is that most experts don’t trust all the official statistics to give them an accurate read on what’s happening. Instead they look for the most reliable figures – which are, necessarily, the figures that will suffer least from under-reporting. That leads them to the figures for homicides. These suffer less from under-reporting, simply because it’s hard to avoid people noticing when someone dies.

- And so to women. The homicide indicators suggest Australian femicide – homicide of women – has fallen over the past three decades at a speed that might surprise many people. Among the most reliable indicators is intimate partner homicide; female victims are down 60+% in the 33 years to 2023-23. See the graph below. (Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, based on figures from the Australian Institute of Criminology’s National Homicide Monitoring Program)

Intimate partner homicide, 1989-90 to 2022-23

Rate per 100,000 population aged 18 years and over

Figure from AIC NHMP

-

- This slow collapse is honestly amazing, because it came after four decades of rising homicide rates, including a big rise in the 1970s. If you had told me in 1990 that the future of intimate partner homicide would be the sort of decline pictured above, I would have been pretty sceptical, but also excited that things were going to get so much better.

- Here’s where the statistical analysis gets more complicated. The Australian Institute of Criminology has released new figures recently (since this post went public, in fact – thanks to Jenna Price for alerting me to this). These figures bring our data up to June 2023.

- These new figures show an uptick in 2022-23. You might take this as saying that intimate partner femicides have been rising. On the other hand, a look at the graph above suggests that bigger jumps in the rate occurred in 90-91, 92-93, 94-95, 2001-02, 05-06, 07-08 and 11-12. This data is just jumpy from year to year, because we’re dealing with quite small numbers by statistical standards. In 2022-23, intimate partner femicide claimed 34 victims – few enough to complicate any year-to-year analysis.

- To quote Ben Spivak at the Swinburne Centre for Forensic Behavioural Science : “We have to be careful in drawing conclusions about year-to-year changes in homicide. Given the small underlying numbers, small changes in the number of homicides can be made to look larger than they are when reported as percentage change.”

- This caution obviously applies even more so to the four months at the start of 2024, where it is occasionally claimed that femicide has reached epidemic levels. News reports on the Anzac Day 2024 weekend featured a figure of “26 women allegedly killed by men in the first 115 days of the year”.That figure presumably includes both intimate partner femicide and other killings of women.

- I don’t know how reliable that number is. But on my initial maths, if that rate of homicide continued right through 2024, it would mean 83 female victims of homicide for Australia this year – a rate of .59 female homicides per 100,000 women. Those 83 deaths – worse than one every five days – are way too high. They are not notably out of line with other recent years, such as 2020-21’s 69; indeed, they are consistent with a continued gradual fall. The .59 rate would have been a record low just a few years ago. And even if the figures jump again this year, it’s not clear what we should make of it: for instance, the figures leapt for a couple of years in a row in the early 2000s, and then just resumed their slide.

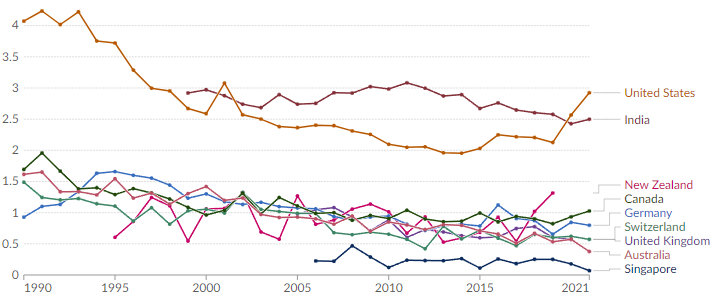

- When we step back and look at other countries, Australia seems to have done well by global standards at reducing violence against women. The femicide rate is falling in many places around the world (as shown in the graph below). But not that many places have bettered Australia’s rate of change over the past 15 years. At the same time, we shouldn’t pat ourselves on the back too hard – because we really just don’t know what causes violent crime numbers to move around over the decades in any country, ours included. (Note that this graph goes only to 2021 and does not include the updated figures described above.)

Female homicide rate, 1990 to 2021, per 100,000 women, for Australia and comparator nations

Figure from Our World In Data

- This graph of the female homicide rate also underlines another point: it is possible to push the rate much lower than Australia’s currently is. Singapore has done it. One question is how much we would be willing to change the nation’s culture to replicate Singapore’s performance. (That country’s law enforcement regime is … tough. That said, my own view is that an obvious place to toughen Australia’s regime would be in enforcement of various court orders around men’s violence against women.)

- We do have one more fairly reliable source of domestic violence data – the Personal Safety Survey done every five years by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. This tries to avoid the police crime figures issues by coming at the problem from the other end: it asks members of the general public what crimes they have experienced. As Swinburne’s Ben Spivak notes, the survey numbers suggest at worst that overall domestic violence rates are not rising, and at best that they are falling over time. For instance, the rate of cohabiting partner violence against women reported in the Personal Safety Survey fell from 1.7% in 2016 to 0.9% in 2021-22. (We don’t have more recent numbers; it’s a five-year survey.)

- Some people cite police crime data to argue that the analysis above goes astray. This argument says that rises over the past decade in rates of male offending in categories like “sexual assault and related offences”, “abduction and harassment” and “acts intended to cause injury” suggest these types of male violence against women are moving up, even as homicide rates move down. That is, they argue that changes in reporting rates don’t explain these numbers. They also point to the past 16 months of intimate partner homicides, where the trend seems to have been up.

- It’s possible that they’re right. But it does not seem all that likely to me that medium-term homicide has detached itself so thoroughly from other medium-term violence indicators.

- The most likely explanation for rises in these categories seems to me likely to be that the official levels of these non-homicide offences are rising because our efforts to raise reporting, charging and conviction rates are actually bearing fruit – that is, less crimes are slipping through the cracks. Most analysts of crime statistics are wary of police-generated statistics for just this reason. But it is always possible that some of the figures reflect real trends in underlying crime. This is a point that I want to explore further and if necessary revise in this post.

To the extent that the homicide indicators a) indicate actual crime levels and b) are at odds with people’s perceptions, commentators and the media should work to make both the figures and people’s perceptions more accurate. The stories we tell about crime rates have a real impact on people’s lives. As crime academics Terry Goldsworthy and Gaell Brotto have noted, a person’s fear of current crime levels can be influenced by a number of things, including media exposure. Don Weatherburn, former head of the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, has complained: “The female homicide rate is much lower now than it was 20 years ago. The media never report this.”

All the above parsing of crime statistics may seem like nit-picking, or even like an apology for domestic violence. (I’ve been accused of both since writing the original version of this post.)

But such dismissals are foolishness. Crime statistics represent our best way to find out what’s going on in the world. The alternative is to try to discuss crime by having people talk only about what their friends down the pub reckon (“mate, this whole violent crime thing is a made-up problem/out of control”) or what they saw on a TV show last week (“look, it’s obvious the real problem is immigrants/keeping the dole too low/30 years of letting crime run rampant”). Crime statistics matter every time some politician or commentator, left or right, makes a claim about the violent crime rate. They matter even more when policymakers start to talk of changing laws.

Yes, it’s possible that the male-on-female violence trend has turned for the worse in the past 18 months. But on these numbers, that is not yet obvious. We still seem to me to be in a new era of lower crime. The debate should recognise that fact. And at the same time we should work towards the next era, when crime rates can be lower still.

* The author studied criminal statistics at the University of Adelaide and has dealt with statistics and their presentation in various roles for more than 30 years.

This post has been update several times since its first posting, as new data has come to hand.

Thanks to Dr Ben Spivak for checking over some of my conclusions; any errors remain my own. Please let me know if you spot any.