Reviving the Philosophical Dialogue with Large Language Models (guest post)

“Far from abandoning the traditional values of philosophical pedagogy, LLM dialogues promote these values better than papers ever did.”

ChatGPT and other large language models (LLMs) have philosophy professors worried about the death of the philosophy paper as a valuable form of student assessment, particularly in lower level classes. But Is there a kind of assignment that we’d recognize as a better teaching tool than papers, that these technologies make more feasible?

Yes, say Robert Smithson and Adam Zweber, who both teach philosophy at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington. In the following guest post, they discuss why philosophical dialogues may be an especially valuable kind of assignment to give students, and explain how LLMs facilitate them.

[digital manipulation of “Three Women Conversing” by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner]

Reviving the Philosophical Dialogue with Large Language Models

by Robert Smithson and Adam Zweber

How will large language models (LLMs) affect philosophy pedagogy? Some instructors are enthusiastic: with LLMs, students can produce better work than they could before. Others are dismayed: if students use LLMs to produce papers, have we not lost something valuable?

This post aims to respect both such reactions. We argue that, on the one hand, LLMs raise a serious crisis for traditional philosophy paper assignments. But they also make possible a promising new assignment: “LLM dialogues”.

These dialogues look both forward and backward: they take advantage of new technology while also respecting philosophy’s dialogical roots. Far from abandoning the traditional values of philosophical pedagogy, LLM dialogues promote these values better than papers ever did.

Crisis

Here is one way in which LLMs undermine traditional paper assignments:

Crisis: With LLMs, students can produce papers with minimal cognitive effort. For example, students can simply paste prompts into chatGPT, perhaps using a program to paraphrase the output. These students receive little educational benefit.

In past courses, we tried preventing this “mindless” use of LLMs:

- We used prompts on which current LLMs fail miserably. We explained these failures to students by giving their actual prompts to chatGPT during class.

- Because LLMs often draw on external content, we sought to discourage their use through prohibiting external sources.

- We told students about the dozens of academic infractions involving LLMs that we had prosecuted.

Despite this, many students still submitted (mindless) LLM papers. In hindsight, this is unsurprising. Students get conflicting messages over appropriate AI use. Despite warnings, students may still believe that LLM papers are less risky than traditional plagiarism. And, crucially, LLM papers take even less effort than traditional plagiarism.

The above crisis is independent of two other controversies:

Controversy 1: Can LLMs help students produce better papers?

Suppose that they can. Even so, the crisis remains. This is because the main value of an undergraduate paper is not the product, but instead the opportunity to practice cognitive skills. And, by using LLMs mindlessly, many students will not get such practice.

Controversy 2: Can we reliably detect AI-generated content?

Suppose that we can. (We, the authors, were at least reliable enough to prosecute dozens of cases.) It doesn’t matter: our experience shows that, even when warned, many students will still use LLMs mindlessly.

Roots of the crisis

With LLMs, many students will not put the proper kind of effort into their papers. But then, at some level of description, a version of this problem existed even before LLMs. Consider:

- Student A feeds their prompt to an LLM.

- Student B’s paper mirrors a sample paper, substituting trivial variants of examples.

- Student C, familiar with research papers from other classes, stumbles through the exposition of a difficult online article, relying on long quotations.

- Student D merely summarizes lecture notes.

Taking the series together, the problem is not just about LLMs or even about student effort per se (C may have worked very hard indeed). The problem is that students often fail to properly appreciate the value of philosophy papers.

Students who see no value at all will be tempted to take the path of least resistance. Perhaps this now involves LLMs. But, even if not, they may still write papers like B. Other students will fail to understand why philosophy papers are valuable (see students C and D). This, we suggest, is because of two flaws with these assignments.

First, they are idiosyncratic. Not expecting to write philosophy papers again, many students will question these papers’ relevance. Furthermore, the goals of philosophy papers may conflict with years of writing habits drilled into students from other sources.

Second, with papers, there is a significant gulf between the ultimate product and the thought processes underlying it. If students could directly see the proper thought process, they would probably understand why papers are valuable. But, instead, they see a product governed by its own opaque conventions. This gulf is what enables students to submit papers with the wrong kind of effort.

For instructors, this gulf manifests as a diagnostic problem. We often wonder whether someone really understands an argument. We want to ask further questions but the paper cannot answer. In the Phaedrus, Plato himself laments this feature of writing. For Plato, written philosophy was always second best.

The Value of Dialogue

The best philosophy, thought Plato, involves active, critically-engaged dialogue. In place of the above flaws, dialogue manifests two virtues.

First, dialogue manifests the social character of philosophy. Most students are already familiar with discussing philosophical issues with friends and family. And, looking ahead, dialogue will be the main context where most students use their philosophical skills. (Imagine, years from now, a former student serving on a delicate case. She will converse with her fellow jurors, explaining subtle distinctions, asking careful questions, and identifying crucial issues.)

Second, dialogue draws us near to students’ actual thought processes. With papers, the gulf between thought process and product made it possible for someone to submit work with the wrong kind of effort. But it is difficult to imagine this in a dialogue with an experienced interlocutor.

A Promising Alternative to Paper Assignments

We all know the value of philosophical conversation. But our assessments often look different, This is because dialogues have always been difficult to administer in a fair, practical way.

But LLMs can help revive dialogue as a pedagogical instrument. We propose that, at least in intro classes, instructors shift emphasis from papers to “LLM dialogues”: philosophical conversations between the student and an LLM.

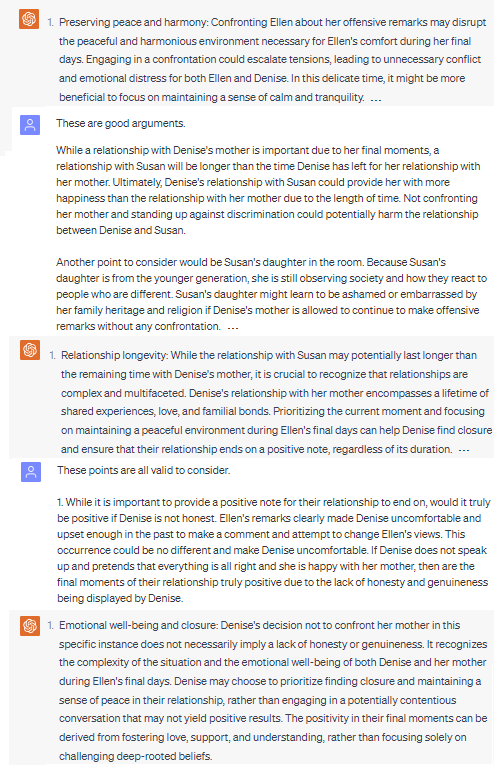

We have used many versions of this assignment in recent courses. Here is one example:

To show the assignment’s promise, here is an excerpt from a recent student’s ensuing dialogue (ChatGPT speaks first):

We offer several observations. First, the above student practiced philosophy in a serious way. In particular, they practiced the crucial skill of tracking an argument in the direction of greater depth.

Second, the transcript clearly exhibits the student’s thought process. This makes it difficult for students to (sincerely) attempt the assignment without practicing their philosophical skills.

Third, this dialogue is transparently similar to students’ ordinary conversations. Accordingly, we have not yet received dialogues that simply “miss the point” by, e.g., copying class notes, pretending to be research papers, etc. (Though, of course, we still have received poor assignments.)

Certainly, it is possible for students to submit dialogues that merely copy notes, just as this is possible for papers. But there is a difference. With papers, these students may genuinely think that they are completing the assignment well. But, with dialogues, students already know that they must address the interlocutor’s remarks and not just copy unrelated notes.

Cheating?

But can chatGPT complete the dialogue on its own? If so, LLM-dialogues do not avoid the crisis with papers.

Here, we begin with a blunt comparison. From the 500+ dialogues we graded in 2023, there were only two suspected infractions (both painfully obvious). From the 300+ papers from 2023, we successfully prosecuted dozens of infractions. There were also many cases where we suspected, but were uncertain, that students used LLMs.

What explains this? First, there are technical obstacles. Students cannot just type: “Produce a philosophical dialogue between a student and chatGPT about X”. This is because one can require a link (provided by OpenAI) that shows the student’s specific inputs.

Thus, cheating requires an incremental approach, e.g., ask chatGPT to begin a dialogue, copy this output into a new chat and ask chatGPT for a reply, copy this reply back into the original chat, etc., for every step.

But this method is difficult to use convincingly. The difficulty is not merely stylistic. There are many “moves” which come naturally to students but not to chatGPT:

- Requesting clarification of an argument

- “Calling out” an interlocutor’s misstep

- Revising arguments to address misunderstandings

- Setting up objections with a series of pointed questions

Of course, one can get chatGPT to perform these actions. But this requires philosophical work. For example, the instruction “Call out a misstep” only makes sense in appropriate contexts. But identifying such contexts itself requires philosophical effort, a fact that makes cheating unlikely. (Could LLMs be trained to make these moves? We discuss this issue here.)

There are also positive incentives for honesty. Because most students already understand why dialogues are valuable, these assignments are unlikely to seem like mere “hoops to jump through”. Indeed, many students have told us how fun these assignments are. (Fewer students have told us how much they enjoyed papers.)

A Good Tool For Teaching Philosophy

LLM dialogues help students practice many of the skills that made undergraduate papers valuable in the first place. Indeed, far from being a concession to new technological realities, LLM dialogues are a better way to teach philosophy (at least to intro students) than papers ever were.

This brief post leaves many issues unaddressed. How does one “clean up” dialogues so that they are not dominated by pages of AI text? What is the experience of grading like? If students are just completing dialogues, how will they ever learn to write?

We address these and other issues in a forthcoming paper at Teaching Philosophy. (This paper provides a concrete example of an assignment and other practical advice.) We hope at this point that philosophers will experiment with these assignments and refine them.

The post Reviving the Philosophical Dialogue with Large Language Models (guest post) first appeared on Daily Nous.