How the Battle of the Sexes sheds light on the battle of the sexes

If you’ve studied game theory, you’ve probably come across the mixed-motive coordination game, a simple one-shot game in which two representative actors have to figure out how to coordinate so as to find a mutually beneficial equilibrium – but have different interests over which equilibrium they choose. And if you studied it a couple of decades ago, you very likely have heard it referred to as “the battle of the sexes,” a term that has fallen out of common usage, for obvious reasons. But when I read Tyler Cowen’s short piece on the actual historical struggle between women and men for recognition, I was immediately was reminded of Jack Knight’s argument, based on mixed-motive coordination games, for why power is more important to the emergence of social rules than most economists think.

Tyler’s brief claim is as follows:

It’s interesting to think of Mill’s argument as it relates to Hayek. So Mill is arguing you can see more than just the local information. So keep in mind, when Mill wrote, every society that he knew of, at least treated women very poorly, oppressed women. Women, because they were physically weaker, were at a big disadvantage. If you think there are some matrilineal exceptions, Mill didn’t know about them, so it appeared universal. And Mill’s chief argument is to say, you’re making a big mistake if you overly aggregate information from this one observation, that behind it is a lot of structure, and a lot of the structure is contingent, and that if I, Mill, unpack the contingency for you, you will see behind the signals. So Mill is much more rationalist than Hayek. It’s one reason why Hayek hated Mill. But clearly, on the issue of women, Mill was completely correct that women can do much better, will do much better. It’s not clear what the end of this process will be. It will just continue for a long time. Women achieving in excellent ways. And it’s Mill’s greatest work. I think it’s one of the greatest pieces of social science, and it is anti-Hayekian. It’s anti-small c conservatism.

Tyler frames the dispute in a Hayekian way. Unpacking his argument (I think this is right, but am happy to listen to corrections), the Hayekian perspective is that we want information that will allow people to coordinate productively. Hayek suggests that this information is most likely to guide outcomes in “spontaneous orders” like the market, where people can figure out, without very much external constraint, what the rules of interaction ought to be. Better rules will emerge through an unguided evolutionary process within a broader constitutional order, whose main function is to guard against forces that might disrupt this spontaneity.

Tyler points out out that this Hayekian framework is missing something big with respect to gender relations. Spontaneous orders have historically involved a lot of discrimination against women, who are physically weaker than men, and less able to defend their interests. J.S. Mill argued, on the basis of a non-Hayekian rationalist logic, that women would be able to achieve far more if various contingent rules discriminating against them unraveled, so that women’s rights to engage fully and equally were protected. And, Tyler concludes, Hayek has turned out to be very wrong, while Mill has turned out to be absolutely right, on this particular point.

But you can also think about this in a non-Hayekian framework, that of simple game theory. More pertinently – and this is the argument of a great short piece by Jack Knight (slightly imperfect scan here – I’ll try to get a better one when I next get close to a proper scanner), you can think of it within a mixed motive coordination framework. The Battle of the Sexes game can, despite its crude and stereotypical framing, be used to shed light on the battle of the sexes.

Jack’s piece is less well known than it should be, because it appears as a chapter in an edited volume. It summarizes and clarifies the argument that he makes in his much better known book, Institutions and Social Conflict in some very nice ways. What it suggests is that Tyler’s criticism of Hayek can be generalized. Spontaneous order arguments (which rely on evolution), and arguments more generally that private actions lead to superior outcomes, are special cases of a more general framework. They are likely to work best when people are indifferent between the possible outcomes, or where power disparities between people are negligible.

To understand this, let’s start with the mixed motive coordination game itself. The miracle of Google Image Search reveals a version of the Battle of the Sexes game on an economics education website, in all its unreconstructed and awful glory, in which “MAN” dukes it out with “WOMAN” over whether or not they should should both go to the “Boxing” game, or just go “Shopping” instead.

![]()

Happily, you can substitute out the crude gender assumptions without changing the math. Let’s assume instead that two individuals, with non gender specific names, Pat and Lindsay, are in a relationship. They disagree over how they should spend a night out, even if they both love each other and agree that they want to spend it together. For boxing and shopping we can substitute in – I don’t know – Dungeons and Dragons versus going to an arthouse movie – or whatever other pair of alternative activities you like.

The payoffs in this game reflect the facts that (a) both actors are better off coordinating, and (b) that they have different preferences over how they coordinate (that is why it is mixed motive coordination). Both Pat and Lindsay have higher payoffs when they coordinate on the same strategies than when they don’t. Indeed, if they fail to coordinate, each of them gets the “breakdown values” with zero payoffs. However, they disagree over what they should coordinate on. Perhaps Pat prefers Dungeons and Dragons (they get a payoff of 2, and Lindsay gets a payoff of 1), while Lindsay prefers the arthouse movie. In short, they have shared incentives to coordinate, but clashing incentives over which strategies they should coordinate on

What Jack does, in the chapter that I’ve linked to, is to suggest that this simple game tells us a lot about where informal institutions come from, and how they work. There are a lot of informal institutions in human societies – informal rules that aren’t laid down by the government, but that are pretty pervasive. Think about how people queue in different countries. Think also – to make the stakes clearer – about the informal but harshly enforced expectations that Black people would make way for White people if they encountered each other on the sidewalk in the pre-Civil Rights South.

Jack suggests that these informal rules and social institutions are the culmination of a myriad of mixed motivation interactions. To illustrate this, we can apply the battle of the sexes framework to the actual battle of the sexes that Tyler highlights. We can stick with the players who are identified as MAN (here, some representative man in a given society) and WOMAN (here, some representative woman), but with quite different valences. Instead of reproducing cliches (those women, they love their shopping!), we can use this framework to ask about the deep processes that the cliches arise from. Where does the norm that women ought focus on household duties arise from? Why, more generally, do many norms emerge that restrict the activities of women, while providing an expansive role for men?

As Jack notes in his book, across a wide variety of societies, “informal rules have structured relationships between men and women in such ways as to produce long-term distributional differences.” In non-academic language, informal norms have emerged across many societies that disadvantage women in multiple ways (e.g. denying them full property ownership, or ability to participate in public life). And Jack’s argument is that these rules have emerged from many, many interactions between men and women, in which men systematically had the upper hand. The battle of the sexes is played again, and again, and again, between different men and different women. And as it is played repeatedly, shared expectations emerge, which then become informal rules, that everyone ‘knows,’ even if they do not necessarily like them.

The key to this argument is the breakdown values – the payoffs that actors get if they don’t coordinate in a mixed motive interaction. In the simple game above, these payoffs are symmetrical: everyone gets zero payoff if they fail to coordinate. But what if the payoffs are asymmetrical? In other words, what if one actor ends up only mildly worse off if there isn’t coordination, while the other ends off much worse off? In the actual battle of the sexes in most societies, women plausibly faced much worse outcomes than men, when they disagreed over something important. In the best case, women probably had much fewer or much worse outside options. In the worst case, they faced the threat of violence or death if they persisted in doing things that men would prefer they didn’t do.

The argument, then, is that these differences in breakdown options make it much harder for women to bargain hard for what they want, and correspondingly much easier for men. Both sides know that the woman will be much worse off than the man if they fail to reach agreement. And that in turn means that they are much more likely to coordinate on the strategies that favor the man.

As men and women engage in this kind of interaction, again, and again and again, they set general expectations which in turn lead to informal rules. Women figure out, as a class, that they are likely to end up worse off if they disagree with men, and men are able to make them back down. Norms emerge in a decentralized way that systematically favor the more powerful actor, and disfavor the less powerful one.

As a result, the rules that emerge from spontaneous orders are likely to reflect the power asymmetries within them. Such asymmetric rules are adhered to not because they are legitimate in any meaningful way, or necessarily deeply internalized, but because the disfavored individuals expect that they will be worse off if they don’t abide by them.

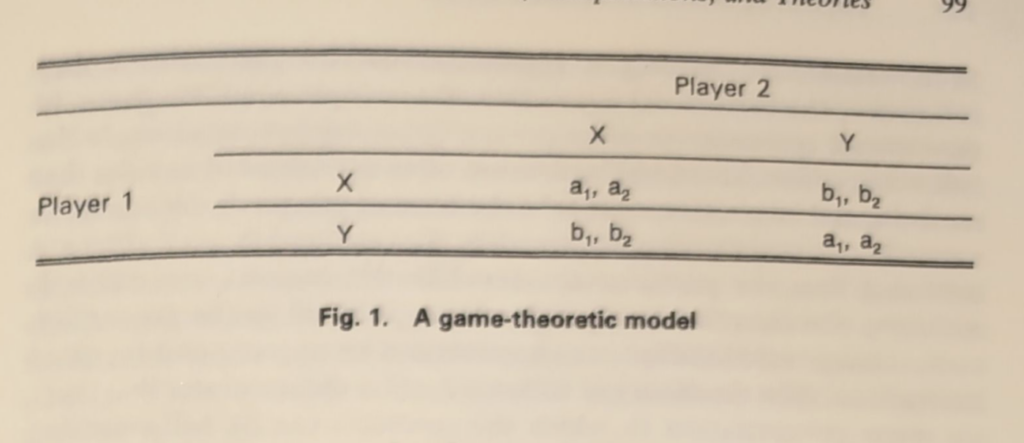

And this can be generalized. The kinds of evolutionary arguments that Hayek makes (e.g. that in a spontaneous order, rules will evolve that are to our broad advantage), and the transaction cost arguments made by institutional economists such as Williamson and North turn out to be special cases of the mixed-motivation framework. This can be seen if you look at a more generalized version of the 2×2 framework, where two players, Player 1 and Player 2 each have two strategies, X and Y.

If a1 is higher than b1, and a2 is higher than b2, then this is some kind of coordination game. Both players are better off converging on an outcome where they match strategies, playing X, X, or Y, Y, and getting the higher payoffs. If they play X,Y or Y, X they both end up with worse payoffs.

Jack argues that evolutionary accounts like Hayek’s will work best when a1 is equal to a2. That is, they are really arguments about pure coordination rather than mixed motive coordination. If neither Player 1 nor Player 2 really cares about which outcome they coordinate on – all that matters is that they agree – then the evolution of norms will be a relatively uncomplicated process. Whether it ends up at X,X or Y,Y will be arbitrary and possibly stochastic, since no-one is going to have any particular incentive to struggle or to disagree. The classic example of a pure coordination game is that of deciding which side of the road people should drive on – no-one cares much whether the rule says that it is on the left side or the right side, so long as there is a rule, and everyone knows it.

He argues that transaction costs accounts, like Williamson’s or North’s (some of the time: Doug was a colleague and occasional collaborator of Jack’s and sometimes shifted position) are often most plausible when b1=b2. These accounts predict that economic institutions will tend to be efficient – they will minimize transaction costs. Jack suggests that such institutions will only emerge in the absence of power asymmetries – that is, when the breakdown values of both actors are much the same. Under those circumstances, it will be impossible for one actor to use credible threats to force another to accept an outcome that it doesn’t prefer. Without power asymmetries, inefficient institutions, which benefit the more powerful actor at the cost of lower overall gains, are unlikely to emerge or persist.

For just the same reason, when there are significant power asymmetries, we are likely to see the opposite outcome – persistent inefficient institutions that benefit the powerful at the expense of overall wellbeing and efficiency. Indeed, Jack’s framework suggests that both evolutionary accounts and transaction cost accounts of institutional emergence and change are no more than special cases of a broader approach that does not assume either as a general matter that actors are indifferent between outcomes, or that actors have relatively equal bargaining power. Much, and likely most of the time, actors will have different interests (they will prefer to coordinate on different outcomes), or different levels of bargaining power (some will be much worse in the case of breakdown than others), or both.

In other words, power matters a whole lot. I suspect Tyler won’t agree with this claim – but Jack’s framework suggests that Hayek’s blind spot about women isn’t a special casem and instead a more general blind spot. Spontaneous orders and decentralized bargaining are only likely to lead to attractive informal rules under highly specific circumstances. And creating those specific circumstances will likely require a lot more social engineering than Hayek would be comfortable with. The JS Mill claim about women can be made pari passu about a whole variety of other groups who find themselves informally discriminated against across a wide variety of circumstances (and women still have to deal with powerful structural forces of discrimination, even if their prospects are now much better).

Two final points. One is that this argument (made in various forms in the late 1980s and early 1990s) speaks to a much more recent emerging literature that asks about the relationship between power and emergent informal norms. This paper by Suresh Naidu, Sung-Ha Hwang and Sam Bowles is one example. Liam Kofi Bright, Nathan Gabriel and Cailin O’Connor’s recent piece on the stability of racial capitalism is another. And one day, for that matter Cosma and I might harpoon our own Great White Whale paper and bring the proceeds into port (we do have a different piece on a very different topic coming out soon).

The other is that there are other aspects of Hayek’s arguments about spontaneous orders that only partly fit with this account. He suggests that they don’t just lead to better rules but better discovery. There is more to be said about this (and in particular the aristocratic elements), but that would require a post of its own.