Sunday, 19 December 2021 - 7:59pm

This month, I have been mostly drinking too much, but I also read a few things:

- Cuba’s Vaccine Could End up Saving Millions of Lives — Branko Marcetic in Jacobin:

After a dire twelve months, when a too hasty reopening sent the pandemic surging, deaths peaking, and the country back into a crippling shutdown, a successful vaccination program has turned the pandemic around in the country. Cuba is now one of the few lower-income countries to have not only vaccinated a majority of its population, but the only one to have done so with a vaccine it developed on its own. The saga suggests a path forward for the developing world as it continues struggling with the pandemic in the face of ongoing corporate-driven vaccine apartheid, and points more broadly to what’s possible when medical science is decoupled from private profit. According to Johns Hopkins University, as of the time of writing, Cuba has fully vaccinated 78 percent of its people, putting it ninth in the world, above wealthy countries like Denmark, China, and Australia (the United States, with a little below 60 percent of its population vaccinated, is ranked fifty-sixth). The turnaround since the vaccination campaign began in May has revived the country’s fortunes in the face of the twin shocks of the pandemic and an intensifying US blockade.

- In Praise of One-Size-Fits-All — Lawrence B. Glickman in the Boston Review:

In his second inaugural address, FDR celebrated government as an institution that “has innate capacity to protect its people against disasters once considered inevitable, to solve problems once considered unsolvable.” For decades after he died in 1945, the federal government showed itself to be capable of promoting the general welfare not only via programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid and through ambitious infrastructure programs (such as the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956), but in its promotion of civil and voting rights, which, for the first time since Reconstruction, made the United States a true democracy in which all adult citizens had “one-size-fits-all” rights. But as the New Deal order waned, a new ethic emerged that privileged individual choice, denigrated society, denounced public spending, and critiqued the government as sclerotic and increasingly incapable of serving citizens—now often figured as “customers,” “taxpayers,” or “entrepreneurs.” In the process, “one size fits all” migrated from a selling point of modern fabrics to a derogatory term connoting the straitjacket of the autocratic, bureaucratic welfare state. It entered into our political language just as the reigning paradigms of economics (mass production/consumption) and politics (New Dealism) were sputtering. If the phrase signified expansiveness in marketing, it came to stand for constraint in politics. The changing valence of the phrase marks a political transformation with which we are still wrestling.

- Call Corporate Crime Corporate Crime — by the Anonymous (what are they afraid of?) editor of Corporate Crime Reporter:

The section of the Wall Street Journal that covers corporate crime doesn’t use the term. Instead, it’s called Risk & Compliance Journal. NYU Law School has a program to study and report on corporate crime. But they call it the NYU Law Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement. The New York Times prefers the term white collar crime. As does the American Bar Association, which has a White Collar Crime Division. Primary topic of discussion? Corporate crime. Why white collar crime instead of corporate crime? White collar crime includes not just the corporate crime of the bank stealing from millions of customers, but bank tellers stealing from the bank. The implication? Hey, it’s not just corporations. Everybody does it!

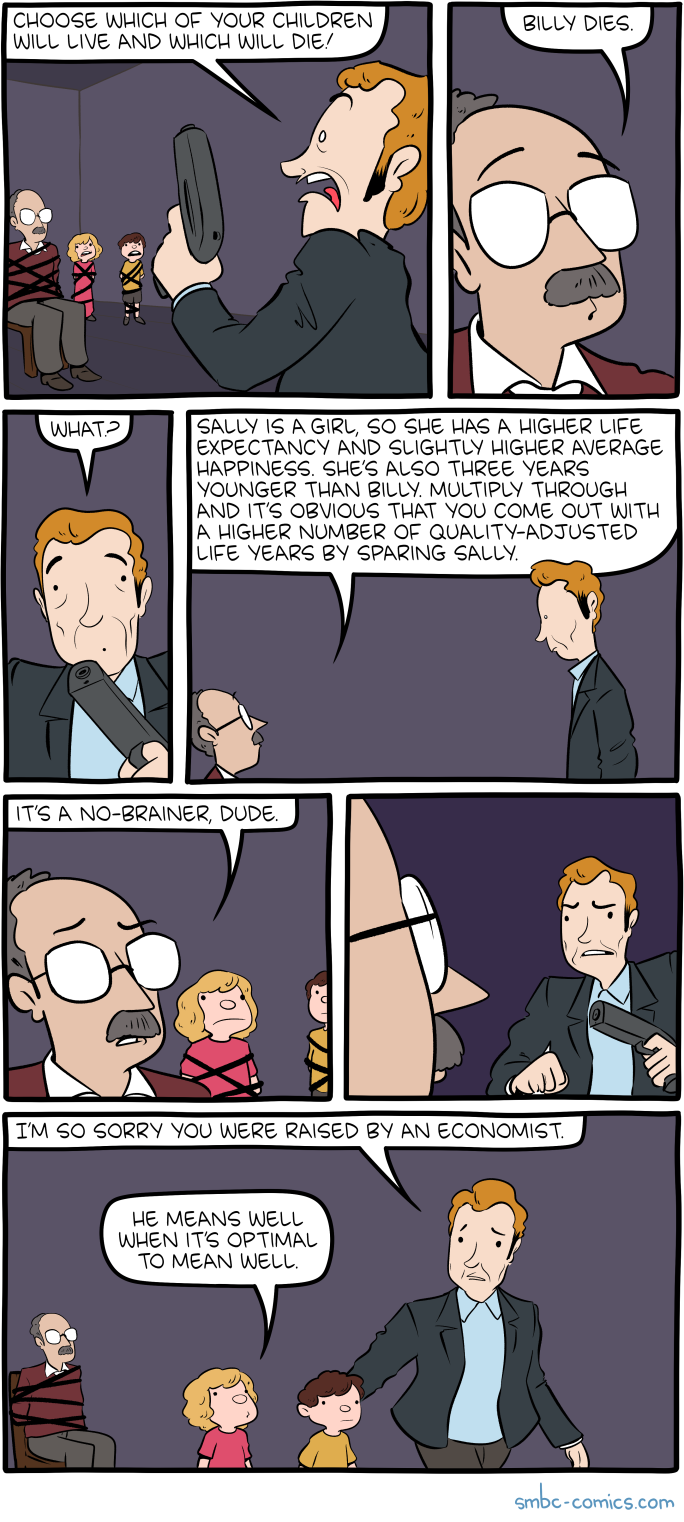

- Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal — by Zach Weinersmith:

- What living with COVID would really mean for Australia — John Quiggin in Independent Australia:

What most people who talk about “living with COVID” in Australia seem to have in mind is something different: a situation where there is a steady but manageable flow of cases, say 1,000 per day in Australia and where a limited set of restrictions is maintained indefinitely. […] Unfortunately, this version of “living with COVID” represents a mathematical impossibility. The reason this is that infections diseases display exponential growth, or contraction, measured by the (effective) reproduction rate — R. If R>1, the pandemic spreads until it runs out of people to infect and if R<1, it contracts until the number of cases dwindles to zero, or there is some new introduction. […] What this means is that a stable number of cases can only be maintained with an unstable policy, involving repeated tightenings and relaxations, just as we have seen in all countries that have chosen to “live with COVID”.