Sunday, 20 September 2020 - 7:14pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- No, Animals Do Not Have Genders — Cailin O'Connor in Nautilus:

How do we know that gender is not simply a biological fact? What makes it cultural, rather than analogous to sex-differentiated behavior in animals? Here is some of the key evidence. Unlike in any other animal, gendered behavior in humans is wildly different across cultures. What is considered appropriate for women in one culture might be deemed completely inappropriate in another. Even the number of genders is culturally variable. While most cultures have settled on two genders, associated with biological sex differences, others settle on three or more. Relatedly, the rules and patterns of gender change over time. While in the early 1900s women in the United States were forbidden from wearing trousers, it is now perfectly acceptable to do so. And while pink is now considered the color of femininity in the Western world, this association only emerged recently. In other words, there is a lot of arbitrariness to gender—it is flexible, it can be done in many ways. And this indicates that it is deeply shaped by culture.

- This Modern World — by Tom Tomorrow:

- How Conspiracy Theories Are Shaping the 2020 Election—and Shaking the Foundation of American Democracy — Charlotte Alter in Time:

When asked where they found their information, almost all these voters were cryptic: “Go online,” one woman said. “Dig deep,” added another. They seemed to share a collective disdain for the mainstream media–a skepticism that has only gotten stronger and deeper since 2016. The truth wasn’t reported, they said, and what was reported wasn’t true. This matters not just because of what these voters believe but also because of what they don’t. The facts that should anchor a sense of shared reality are meaningless to them; the news developments that might ordinarily inform their vote fall on deaf ears. They will not be swayed by data on coronavirus deaths, they won’t be persuaded by job losses or stock market gains, and they won’t care if Trump called America’s fallen soldiers “losers” or “suckers,” as the Atlantic reported, because they won’t believe it. They are impervious to messaging, advertising or data. They aren’t just infected with conspiracy; they appear to be inoculated against reality.

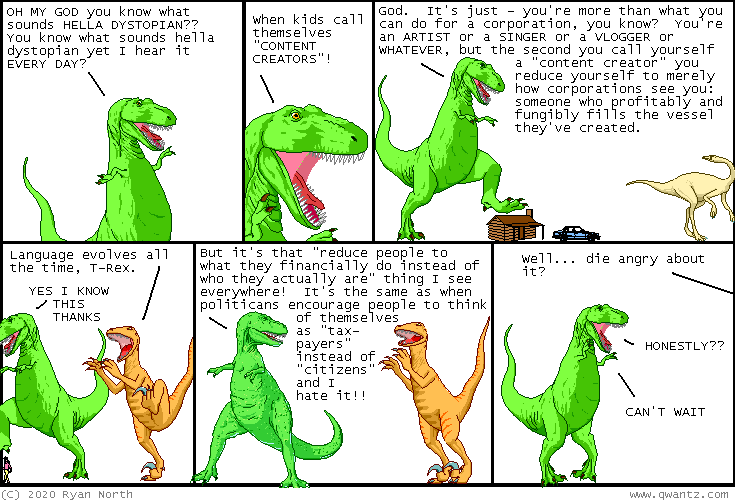

- Dinosaur Comics — Ryan North:

- Night and Day — Fintan O’Toole in the New York Review of Books:

The message is that Biden’s terrible excess of grief leaves him with plenty left over to share with the whole country. […] But when we bring it back to real politics, the notion is at once deeply affecting and highly problematic. On the one hand, there is something appropriate about the image of America as embodied in a man with a deep black hole in the middle of his chest: that hole is a portal through which the Democrats have passed into a language of brokenness and grieving. Perhaps, in this, there is evidence that something has been learned from the debacle of 2016. Trump won in part because both Obama and Hillary Clinton explicitly countered “Make America Great Again” with “America is already great.” It might have seemed like a smart soundbite, but it reeked of smugness and it was, for millions of voters, patently untrue. It relied on the clichés of American exceptionalism that so many citizens knew to be hollow. Trump ruthlessly exploited the gap between the rhetoric and the reality. At least this time, “America is already great” is off limits. Democrats obviously cannot use it when fighting a Republican incumbent, but what is striking now is how stark, how dark, the alternative is. Under the pressure of the political chaos of the Trump presidency, the horrors of the pandemic, the Black Lives Matter protests, and Biden’s mournful persona, the party has embraced a radically different image: of an America that is shattered, sagging under the burdens of mass death, economic disruption, malign government, and national impotence. The Democrats’ battle hymn in 2020 is a De Profundis, a cry from the depths.

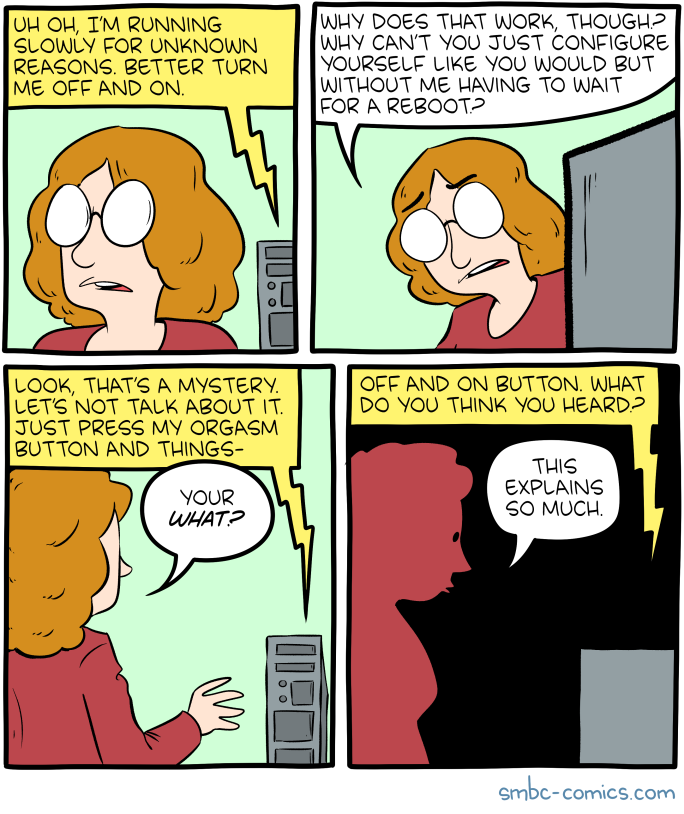

- Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal — by Zach Weinersmith:

- John Stoehr — in Religion Dispatches:

A reporter who spent her life in college prep schools and the Ivy League before moving to Manhattan to work at the Times is vulnerable to media representations of rural life, because they’re media representations created by and for other elites. Fact is, when rural Arizonans talk about “law enforcement” over a plate of eggs and bacon, what they mean is punishing the weak. When they talk about their “liberty,” what they mean is their dominance. When they talk about their “traditional values,” what they mean is their control. A Times reporter can’t possibly know any of that. The problem is made worse when sources give voice to this or that conspiracy theory. She can’t know her sources aren’t delusional. She can’t know they aren’t crazy. She can’t know that conspiracy theories are central to their authoritarian view of the world. So she doesn’t report how dangerous their politics are. She ends up reporting that some Americans believe, for instance, that a “secret cabal” of Democrats and other “radical leftists” in the “deep state” is, in addition to sexually molesting innocent children and perhaps eating them, too, trying to bring down Donald Trump. (This is the QAnon conspiracy you’ve read about lately.) What she should be reporting is that some Americans are willing to say anything to justify any action—violence, insurrection, even treason—to defeat their perceived enemies. Elite reporters, and some non-elite reporters who are following suit, keep talking about conspiracy theories as if they were a “collective delusion.” They are no such thing. The authoritarians who espouse them don’t care if QAnon is true. They don’t care that it’s false. Conspiracy theories are a convenience, a means of rationalizing what they already want to do, which is precisely what elite reporters can’t know and do not report.

- Doonesbury — by Garry Trudeau: