Sunday, 29 September 2019 - 1:52pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

- Non Sequitur — by Wiley Miller:

- Why do people believe the Earth is flat? — Cory Doctorow:

In a pluralistic world, we can aspire to the rule of law, in which rigorous systems keep human frailty in check. In an oligarchic world, we’re left finding people who “sound like they know what they’re talking about” and putting our trust in them. If your people tell you that opioids are killing you (and possibly save your life in the process) and then follow it up by telling you that the Earth is flat or that George Soros wants to weaken your social fabric by funding asylum seekers and paid protesters, well, what yardstick can you measure these statements against?

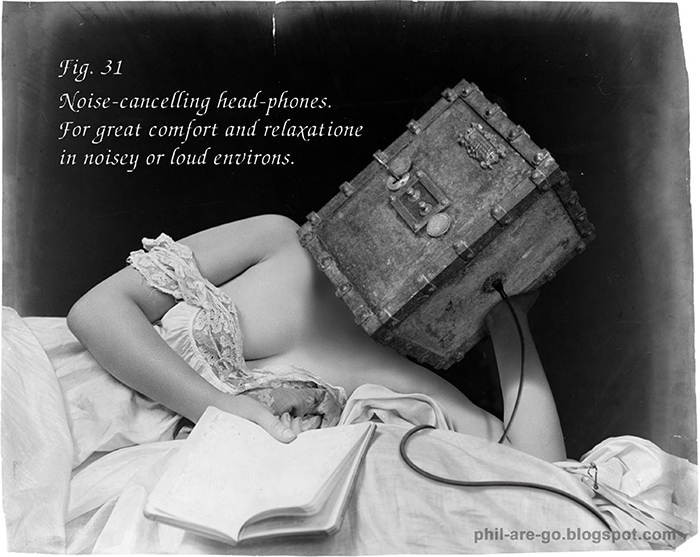

- Noise-canceling headphones, 1902 — Phil Are Go!:

- Boris Johnson can’t be found out: we all know he’s bluffing — Fintan O'Toole in the Guardian:

All governments may end in failure but they are supposed at least to begin with some kind of gravity and some element of faith. As long ago as 1997, Johnson wrote: “Politics is a constant repetition, in cycles of varying length, of one of the oldest myths in human culture, of how we make kings for our societies, and how after a while we kill them to achieve a kind of rebirth.” But King Boris starts out with no clothes. There are no vestiges of solemn dignity to drape the nakedness of his mendacity and fecklessness. The usual arc of a premiership runs from illusion to disillusion, from great expectations to more or less bitter disappointments. Even Theresa May, let us remember, seemed, at this same moment in the cycle in 2016, sincere and serious and deserving of some goodwill. The disillusion took a little while to set in. Johnson cannot disillusion anyone, for no one is under any illusion that he is truthful or trustworthy, honourable or earnest. His fitness for the highest office is not about to be tested – it is the most conspicuous absence in modern British political history.

- Tom Toles:

- Intellectual Debt: With Great Power Comes Great Ignorance — the ever-brilliant Jonathan Zittrain from the Berkman Klein Center:

[…] aspirin was discovered in 1897, and an explanation of how it works followed in 1995. That, in turn, has spurred some research leads on making better pain relievers through something other than trial and error. This kind of discovery — answers first, explanations later — I call “intellectual debt.” We gain insight into what works without knowing why it works. We can put that insight to use immediately, and then tell ourselves we’ll figure out the details later. Sometimes we pay off the debt quickly; sometimes, as with aspirin, it takes a century; and sometimes we never pay it off at all. Be they of money or ideas, loans can offer great leverage. We can get the benefits of money — including use as investment to produce more wealth — before we’ve actually earned it, and we can deploy new ideas before having to plumb them to bedrock truth. Indebtedness also carries risks. For intellectual debt, these risks can be quite profound, both because we are borrowing as a society, rather than individually, and because new technologies of artificial intelligence — specifically, machine learning — are bringing the old model of drug discovery to a seemingly unlimited number of new areas of inquiry. Humanity’s intellectual credit line is undergoing an extraordinary, unasked-for bump up in its limit.

- Off the Mark — by Mark Parisi: