Sunday, 26 May 2019 - 8:27pm

This week, I have been mostly reading:

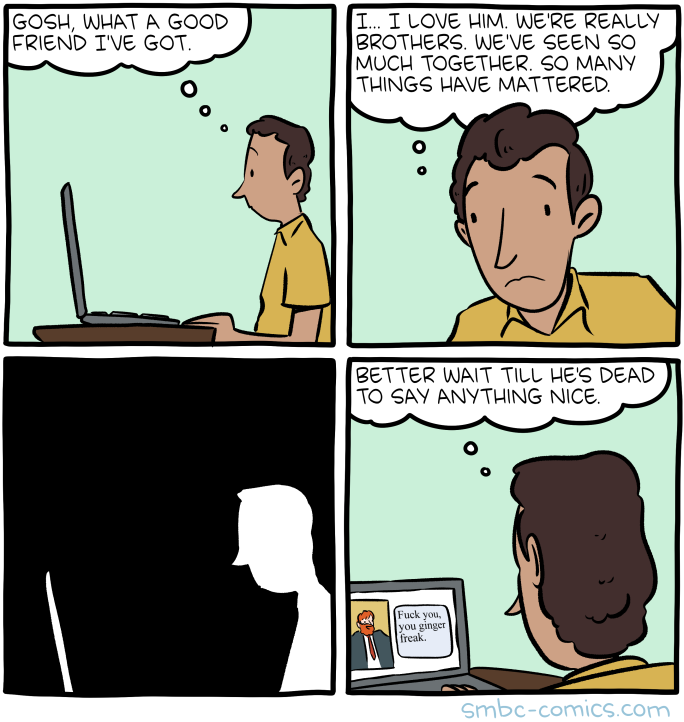

- Friendship — Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal by Zach Weinersmith:

- Love Your Job? Someone May be Taking Advantage of You — by a nameless PR bot at Duke University:

Professor Aaron Kay found that people see it as more acceptable to make passionate employees do extra, unpaid, and more demeaning work than they did for employees without the same passion. “It’s great to love your work,” Kay said, “but there can be costs when we think of the workplace as somewhere workers get to pursue their passions.” Understanding Contemporary Forms of Exploitation: Attributions of Passion Serve to Legitimize the Poor Treatment of Workers is forthcoming in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Kay, the senior author on the research, worked with Professor Troy Campbell of the University of Oregon, Professor Steven Shepherd of Oklahoma State University, and Fuqua Ph.D student Jay Kim, who was lead author. The researchers found that people consider it more legitimate to make passionate employees leave family to work on a weekend, work unpaid, and handle unrelated tasks that were not in the job description.

- Dog breeds are mere Victorian confections, neither pure nor ancient — Michael Worboys in Aeon:

Modern dog breeds were created in Victorian Britain. The evolution of the domestic dog goes back tens of thousands of years – however, the multiple forms we see today are just 150 years old. Before the Victorian era, there were different types of dog, but there were not that many, and they were largely defined by their function. They were like the colours of a rainbow: variations within each type, shading into each other at the margins. And many terms were used for the different dogs: breed, kind, race, sort, strain, type and variety. By the time the Victorian era came to an end, only one term was used – breed. This was more than a change in language. Dog breeds were something entirely new, defined by their form not their function. With the invention of breed, the different types became like the blocks on a paint colour card – discrete, uniform and standardised. The greater differentiation of breeds increased their number. In the 1840s, just two types of terrier were recognised; by the end of the Victorian period, there were 10, and proliferation continued – today there are 27.